Unearthing Ancient Food Secrets: How Stone Kitchens Reveal Culinary History

2025-03-25

Author: Siti

For centuries, the intricate culinary practices of ancient civilizations have been hidden away within the stone kitchens of our ancestors. The modern mortar and pestle you use today are descendants of the manos and metates—stone tools that have endured the test of time and offer insights into the diets of prehistoric peoples across the globe. A mano, a handheld stone implement, works in tandem with the larger metate, a flat stone surface or hollowed-out area in bedrock designed for grinding grains and tubers. Archaeologists have identified bedrock metates that date back an astonishing 15,500 years, making them a treasure trove for understanding ancient food processing methods.

Recent research conducted by a team from the Natural History Museum of Utah seeks to unlock the secrets hidden within these ancient metates. They employ cutting-edge techniques to extract microscopic plant residues preserved in the cracks of these stones, offering valuable information about the diets and lifestyles of the people who once relied on them. Their findings were published last month in the respected journal, *American Antiquity*.

Stefania Wilks, an archaeobotanist and graduate student at the University of Utah, emphasizes the long history of human interaction with the environment in the Western U.S. “People have lived here for time immemorial and have been processing native plants on ground stone tools for a long time too,” said Wilks, highlighting her focus on exploring traditional lifeways and the transformations of landscapes through an analysis of food and medicine sources.

Working alongside Lisbeth Louderback, the Curator of Archaeology at NHMU, Wilks is on a quest to recover plant residues from metates scattered throughout western North America. Their research particularly focuses on starch granules, microscopic structures that serve as energy reserves within plant cells. These granules are incredibly small—some measuring less than a tenth of a millimeter in diameter. By studying them, the researchers aim to unravel the dietary practices of ancient societies.

Metate surfaces may be eroded and exposed to the elements, leading to initial doubts about the survival of plant residues on these tools. However, Louderback's hypothesis suggested that tiny crevices in the metate could house preserved starch granules. “As they ground and mashed food, these starches would have been forced deeper into the stone's surface,” explained Wilks, further emphasizing the hidden layers of culinary history waiting to be uncovered.

The characteristics of bedrock metates vary by region; in Utah, they are often elongated grooves carved into sandstone, while in other areas, they take on circular or dish-like shapes. Regardless of their form, metates tend to be found in groups, hinting at communal cooking and food processing activities.

Wilks notes, “They aren’t as glamorous as artifacts like arrowheads, but they provide essential insights into the plant-based diets of the past.” Particularly interesting are the metates found near basalt outcrops in southern Oregon, where a wealth of culturally significant plants, such as geophytes (root and tuber-bearing species), flourish.

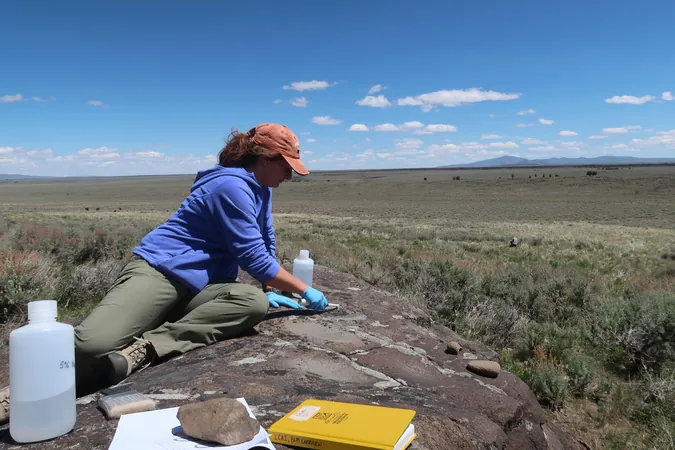

To investigate the usage of these metates, Wilks and her team meticulously compared the surface residues with those found deeper within the cracks of the stones. By using an electric toothbrush and a deflocculant—similar to laundry detergent—they managed to extract deeper plant residues that, to their surprise, yielded hundreds of starch granules, confirming their initial hypothesis about the ancient practices of food processing.

After successfully extracting these granules, the next task was to deduce the species of plants from which they originated. This involved a painstaking analysis of the granules’ morphological characteristics, allowing researchers to identify many granules down to their plant families and, in some cases, to the genus level. Remarkably, they discovered members of the carrot family, particularly a group known as biscuit root, along with wild grasses, likely wild rye, and various plants in the lily family—important staples for Indigenous peoples then and now.

This groundbreaking research not only casts light on the daily lives of ancient communities but also underscores the continuity of traditional practices among Indigenous cultures. What other secrets do these ancient stone kitchens hold? As researchers continue to delve into these historic methods of food preparation, the history of our ancestors becomes ever clearer, connecting past to present in the most delicious way possible.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)