How Pamela Anderson in 'The Last Showgirl' Chronicles the Struggles of Showgirls, Echoing Maureen O'Hara's Bold Stand in 'Dance, Girl, Dance'

2025-01-13

Author: Noah

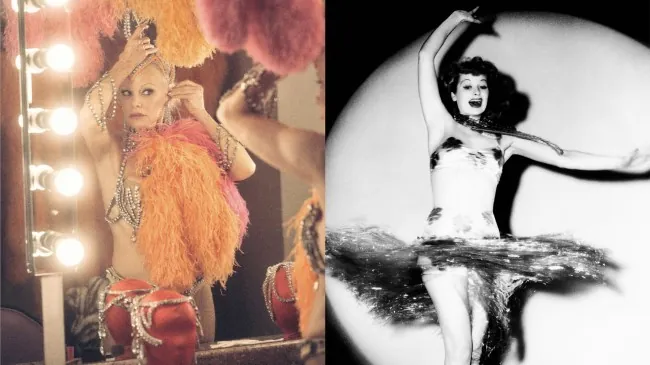

In Gia Coppola’s poignant film, “The Last Showgirl,” viewers are taken on an emotional rollercoaster alongside Shelly, played by Pamela Anderson—delivering what many are calling a career-defining performance. The film captures a week in Shelly's life as she grapples with her identity as a Las Vegas showgirl preparing for what could be her final bow. Highlighting themes of artistic sacrifice and societal undervaluation of women, Coppola’s narrative draws inspiration from a feminist classic, Dorothy Arzner's “Dance, Girl, Dance,” which also spotlights the trials of two showgirls, portrayed by Maureen O'Hara and Lucille Ball.

Both cinematic masterpieces confront the male-dominated capitalist landscape that these women must navigate, where beauty becomes a currency, and the male gaze serves as both a supporter and consumer of their performances. The stark realities of their lives evoke deep questions around worth, aspiration, and the burdens of female artistry.

Coppola looks to establish a tone of anticipation early in “The Last Showgirl,” opening with an empty darkness punctuated by the sound of high heels echoing down a corridor. The focus shifts to Shelly, decked out in a baby pink rhinestone cap and expertly applied makeup. As she engages in playful banter with an unseen interviewer, a humorous yet haunting reality is revealed—age and beauty, once one’s greatest allies, morph into burdens when women are judged solely on fleeting youth.

As the narrative unfolds, the viewers learn that Shelly has dedicated three decades to her craft in a show called “Le Razzle Dazzle,” which is set to close its curtains soon. Despite her long tenure, Shelly’s plight reflects a broader truth: no retirement plan, low expectations, and fractured familial relationships, particularly with her estranged daughter, Hannah.

In “Dance, Girl, Dance,” the introduction of Judy (O'Hara) and Bubbles (Ball) in an Ohio dance troupe draws a parallel to Shelly's world. Their ambitions collide with harsh realities as they maneuver from a charming, albeit shady club to the bright lights of New York City, under the watchful eye of their demanding manager, Madame Lydia Basilova. Each woman, with her distinct approach, illustrates the varying ways show business exploits and empowers.

Arzner’s film stands out not just for its entertainment value, but for its role in empowering women to acknowledge their worth and defy objectification. The pivotal scene in which Judy confronts an audience harassing her during a performance has been recognized as revolutionary. O'Hara’s powerful monologue flipping the male gaze back on the audience challenges societal perceptions of women as mere spectacles for entertainment. The raw vulnerability and conviction displayed during this moment resonate deeply with feminist discourse, highlighting the enduring relevance of these narratives across generations.

Coppola’s “The Last Showgirl” similarly amplifies Shelly’s frustrations as she encounters ageism and sexism while auditioning for the next phase of her life. Despite showcasing her experience and talent, she faces rejection based on superficial criteria. In a moment of defiance, she boldly declares her beauty, even at 57, subverting expectations and reclaiming her narrative.

Unlike the resolutions found in “Dance, Girl, Dance,” where Judy's aspirations are validated, Coppola presents a more sobering reality for women today. The film hints at the stagnation of women's societal positions, especially those aging out of perceived beauty standards—a scenario all too familiar in our contemporary gig economy, where success often seems elusive for those who have dedicated their lives to their craft.

Ultimately, both films shine a light on the venomous consumption of women's artistry and the troubling metrics by which they are evaluated in a patriarchal landscape. As "The Last Showgirl" graces theaters, it prompts crucial discussions about how far we've come and the battles that still lurk beneath the surface. When will society finally recognize that a woman's worth is not merely a function of age or attractiveness, but rather the richness of her experiences and contributions?

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)