Cells Go 'Vomit' Mode to Heal Faster—But at What Cost?

2025-09-13

Author: Noah

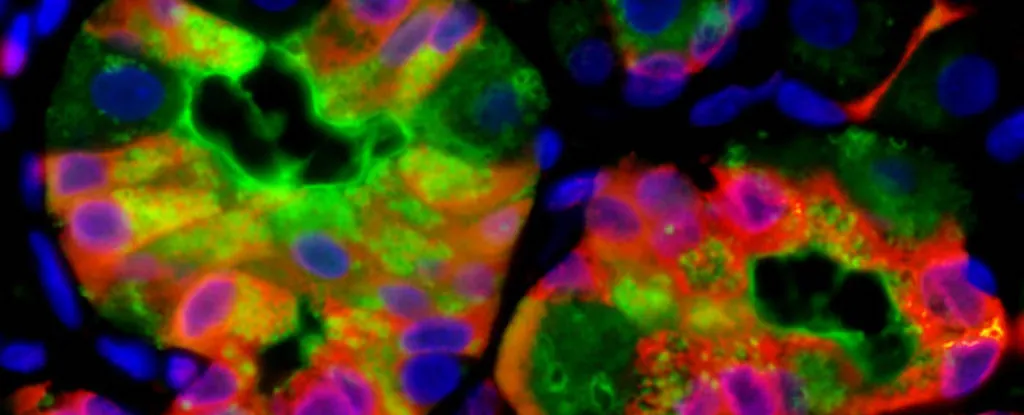

A remarkable new study reveals that injured cells can literally "vomit" out their insides to accelerate healing. While this rapid process is a fascinating cellular strategy, it also raises alarming connections to potential diseases, such as cancer.

Researchers uncovered this phenomenon while exploring paligenosis, where mature cells revert to a younger, stem cell-like state in response to injury. Instead of taking their time to clear out waste, these injured cells can quickly expel their debris in a newly dubbed process called "cathartocytosis," allowing them to rejuvenate and repair more efficiently.

What Happens When Cells Clean House?

According to Dr. Jeffrey W. Brown, a gastroenterologist from Washington University in St. Louis and first author of the study, the aftermath of an injury forces cells to pivot: "The cell's mature machinery for its usual functions can hinder its healing efforts. Thus, this cellular cleanse is a swift alternative to expedite the transition back to a primitive state with the ability to proliferate and mend the damage." The researchers focused on this behavior in the gastrointestinal tract, but suspect it could apply to other body tissues as well.

The process is akin to a quick purge, where cells "vomit" out damaged material, offering a shortcut in their cleanup efforts. Initially, scientists believed this cleanup occurred slowly within lysosomes—cellular organelles tasked with digesting waste. However, they were startled to discover waste accumulating outside the cells during paligenosis, signaling a more rapid method at play.

The Double-Edged Sword of Quick Healing

Using mouse models of stomach injury, the research team confirmed that this vomiting response is a standard part of paligenosis, extending beyond mere coincidence. Yet, this expedited process isn't without its risks. The researchers warn that cathartocytosis can be "speedy but sloppy," and the rapid release of cellular waste could contribute to chronic inflammation and heighten the risk of cancer.

Dr. Jason C. Mills, a senior author and gastroenterologist at Baylor College of Medicine, explained the dangers: "In gastric cells, the reversion to a stem cell state for healing carries significant risks. Aging cells often harbor mutations; if many of these mutated cells revert to stem cell states in attempts to heal, particularly in an inflammatory environment—like during infections—we might see an increased chance of these harmful mutations proliferating and leading to cancer."

A Glimmer of Hope in Understanding Cell Behavior

However, there’s a silver lining. Dr. Brown notes that understanding cathartocytosis could aid in identifying precancerous conditions sooner, paving the way for timely interventions. "If we grasp this process better, we might find ways to enhance the healing response while also preventing damaged cells from pushing the boundaries toward cancer development in chronic injury scenarios," he remarked.

This groundbreaking study opens up new avenues for potential treatments and a deeper understanding of how cells manage stress and repair injuries—but also cautions us to consider the implications of such rapid processes.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)