Unmasking the Hidden Predators: The Battle Against Malaria-Laden Mosquito Larvae in Tanzania

2025-01-09

Author: Mei

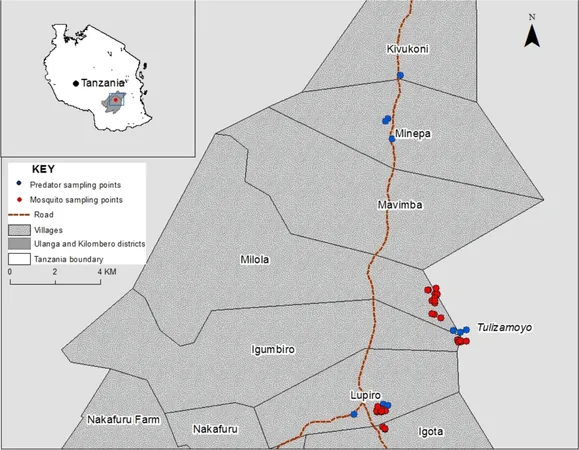

The Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes are infamous as primary vectors of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, affecting millions annually. Their larval stages thrive in various water bodies, where numerous aquatic macroinvertebrate predators lurk, ready to strike. With malaria still a pressing public health issue, understanding these predators' roles could pivotally enhance mosquito control strategies, particularly by harnessing biological control methods. In a groundbreaking study conducted in semi-field conditions in South-Eastern Tanzania, researchers delved deep into the predation behavior and movement of three key aquatic predators: diving beetles, backswimmers, and dragonfly nymphs.

The Experiment: Setting the Stage for Battle

To analyze the effectiveness of these predators, scientists established a network of artificial ponds using two sets of large and small basins. Field-captured predators were introduced to these habitats, where Anopheles arabiensis larvae were deliberately added as prey. Over a 72-hour period, researchers carefully observed the predation rates and mobility of the predators while also monitoring their survival rates.

Key Findings: Who Reigns Supreme?

The findings revealed striking differences in behavior among the predator types. Surprisingly, backswimmers and dragonfly nymphs benefited from the presence of mosquito larvae, showing higher survival rates when prey was available. On the flip side, diving beetles exhibited remarkable mobility, often abandoning habitats devoid of food for those teeming with larvae. Overall, the study quantified predation rates—backswimmers consumed about 7 larvae per day, dragonfly nymphs a staggering 9.6, while diving beetles trailed behind at only 3.2.

Wider Implications: Could Nature's Allies Combat Malaria?

This research draws attention to the urgent need for biocontrol methods in the fight against malaria. Historical reliance on chemical insecticides like DDT and their subsequent environmental consequences have ignited a quest for alternative, sustainable solutions. Utilizing natural predators in mosquito control could not only mitigate the reliance on harmful chemicals but also encourage ecological balance in these aquatic ecosystems.

As insecticide resistance in malaria vectors mounts, the pressing question remains: Could the strategic use of these aquatic predators offer a beacon of hope in the ongoing battle against malaria? Recent studies suggest a necessity for a shift towards integrated vector management strategies, where biological control can complement traditional methods.

A Call to Action: Embracing Ecological Wisdom

The findings of this study are not merely academic; they beckon a pressing call to action. Conservationists, health strategists, and policymakers must draw upon ecological intelligence, integrating natural predator populations into mosquito control regimes. It's time to rethink our approach to malaria prevention and instead leverage the formidable powers of nature to rid the world of its deadliest mosquito adversaries.

The research significantly enhances our understanding of how predator behaviors can shape mosquito populations, paving the way for a new era in malaria control strategies. This battle is ongoing, but with technology and nature in tandem, there remains a glimmer of hope against one of humanity’s oldest foes.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)