Unlocking the Secret: Can Your Genes Protect You from Type 2 Diabetes?

2025-07-03

Author: Yu

New Discoveries in Diabetes Research

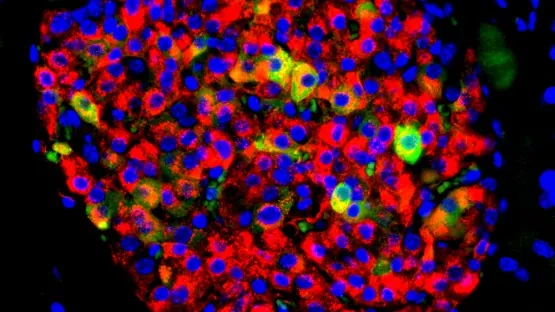

In a groundbreaking study, nutrition scientists are finally clarifying the relationship between Type 2 diabetes and the genes responsible for producing salivary amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch into sugars. Conflicting research has muddled this area for years, but findings published in July offer new hope.

The AMY1 Gene Connection

Researchers have long suspected that individuals with more copies of the AMY1 gene could have an edge against the onset of Type 2 diabetes. This latest study lends credence to that theory, suggesting that increased AMY1 gene copies may provide protection. If future research backs this up, we could be looking at a future where genetic testing at birth helps predict diabetes risk.

Angela Poole, assistant professor of molecular nutrition at Cornell, suggests that knowing one’s genetic risk from birth could profoundly influence health choices, potentially preventing diabetes later in life. This could be a game changer, given the increasing prevalence of the disease.

Understanding AMY1 Variability

The AMY1 gene can appear in multiple copies, ranging from two to as many as twenty. Although the enzyme facilitates the digestion of starches, some experts have raised concerns that better starch breakdown might worsen diabetes. This chronic condition occurs when the body struggles to produce enough insulin or properly respond to it, leading to elevated blood sugar levels.

Addressing Previous Confusion in Research

Previous studies had inconsistent results regarding the correlation between AMY1 copy numbers and diabetes risk. Variations in methodology—some using the qPCR technique while others employed the more advanced digital PCR—led to confusion. Poole’s study found that when conducted correctly, both techniques yielded comparable results for AMY1 copy numbers.

Important Timing Considerations

Another interesting discovery came from measuring salivary amylase activity at different times of the day. Participants showed significantly lower amylase activity in the morning compared to the evening. As Poole explained, this diurnal effect implies that researchers must standardize sample times to obtain accurate readings.

Is More AMY1 Always Better?

The study showed higher salivary amylase activity in individuals with Type 2 diabetes or prediabetes who had more copies of the AMY1 gene. This raises a fascinating question: Could more AMY1 copies actually protect against diabetes, despite initial assumptions that increased starch breakdown might lead to higher blood sugar?

Poole suggests that the body's response during starch chewing may prompt earlier insulin release in those with a higher gene copy number, potentially providing a protective effect. However, she warns that genetic factors alone don’t tell the whole story; dietary habits must also be considered.

Future Research Directions

Poole expresses a strong belief that individuals with fewer AMY1 gene copies could face a higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, contingent upon their starch intake. Comprehensive long-term studies are necessary to further explore the interplay between genes, diet, and diabetes risk.

With researchers like Sri Lakshmi Sravani Devarakonda leading this exciting path forward, we may be on the brink of major breakthroughs in personalized diabetes prevention and treatment.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)