Unleashing the Secrets of Ancient Fish: The Surprising Origins of Teeth

2025-05-21

Author: Ming

Ever winced during a dental cleaning? That sensitivity we feel in our teeth serves a crucial purpose, giving us feedback on temperature, pressure, and even pain while eating. But here's the twist: our teeth's intricate design evolved for an entirely different reason.

Recent groundbreaking research from the University of Chicago has uncovered that the inner layer of our teeth, known as dentin, initially emerged as a sensory tissue within the armored exoskeletons of ancient fish. This doesn’t just change our understanding of teeth; it reshapes our interpretation of evolution itself.

From Armor to Enamel: The Evolutionary Journey of Teeth

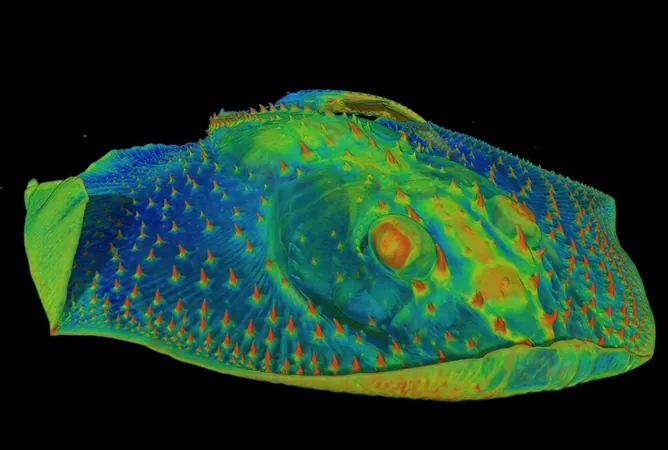

For ages, paleontologists speculated that teeth stemmed from the bumpy structures found on ancient fish armor. However, the actual purpose of these structures remained murky. This new study, published in the prestigious journal Nature, confirms that the dentin-filled armor of a primitive vertebrate fish—dating back around 465 million years to the Ordovician period—was likely designed to sense its aquatic environment.

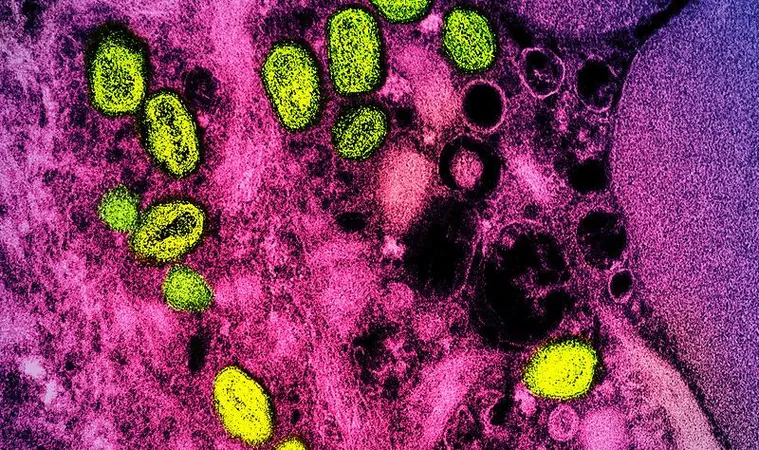

The researchers also unearthed that fossilized structures, commonly regarded as teeth from the Cambrian period (about 485-540 million years ago), bear striking resemblances to sensory organs in modern invertebrates like crabs and shrimp. This suggests a fascinating evolutionary parallel, where diverse creatures developed similar sensory adaptations for survival.

An Unexpected Discovery: From Teeth to Sensory Organs

Neil Shubin, a prominent figure in this research and Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at UChicago, explains, *"Imagine an ancient fish gliding through predatory waters; it needed to detect surrounding conditions. The armor served not just as protection but as a sensory tool in a dynamic ecosystem."* Interestingly, these sensory capabilities are mirrored in today’s armored invertebrates like horseshoe crabs—each evolving a unique approach to interfacing with their environment.

The Journey of Discovery: Scanning Fossils at the Particle Accelerator

Led by postdoctoral researcher Yara Haridy, the study began with a quest to uncover the identity of the earliest vertebrate in the fossil record. Yara scoured museums nationwide, gathering precious Cambrian fossils for CT scans. What started as a side quest soon transformed into a revelation about vertebrate evolution.

Through painstaking CT scanning at the Advanced Photon Source, a night at the particle accelerator turned the tide. Haridy and her team spotted a Cambrian fossil named Anatolepis, revealing hallmark features of vertebrates, including the distinctive tubules indicative of dentin.

A Twist in the Tale: Confounding Expectations

Excitement surged when the team believed they had traced back the first vertebrate tooth-like structure. However, further analysis revealed that what appeared to be dentin was, in fact, akin to the sensory organs found in modern arthropods. Thus, Anatolepis turned out to be an ancient invertebrate, shedding light on the complexity of evolutionary adaptations.

Sensory Armor in Life's Ancient Tapestry

This research highlights that both teeth and sensory structures once served similar functions outside of their modern contexts. Sharks, skates, and even catfish sport tooth-like structures, known as denticles, deeply connected to their nervous systems. Haridy noted, *"These early vertebrates had structures remarkably similar to today’s armored fish and arthropods, underscoring a shared evolutionary trajectory.”*

Revisiting Theories: A New Perspective on Tooth Evolution

The study reignites the debate on how teeth evolved, pitting the 'inside-out' hypothesis against the 'outside-in' theory. The findings support the latter, suggesting that the sensitive structures from exoskeletons laid the groundwork for modern teeth.

Though the search for the earliest vertebrate continues, Shubin reflects on the journey fondly. *"We might not have found what we initially sought, but what we discovered rewrites the narrative of evolution. That’s the beauty of science—one question often leads to more extraordinary answers.”*

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)