Traffic Revolution: How Singapore's ERP System Is Transforming Urban Mobility Worldwide

2025-03-21

Author: Mei

Singapore –

Are you tired of spending countless hours stuck in traffic? If so, you're not alone. Cities around the globe are grappling with debilitating congestion, costing drivers in places like Dublin and Manila over 100 hours a year in rush hour delays. Even closer to home, Singaporeans lost an average of 63 hours in traffic just last year, according to data from technology firm TomTom.

As car ownership continues to rise, Singapore has adopted innovative strategies to tackle traffic woes head-on. The Republic’s two-pronged approach began with the introduction of the Certificate of Entitlement (COE) system in 1990, coupled with the pioneering Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) from 1975. While the COE is a uniquely Singaporean concept, the concept of congestion pricing has spread internationally, most notably in major metropolises seeking effective traffic management.

A Trailblazer in Congestion Pricing

"Singapore was the first city in the world to implement road congestion pricing," claims Dr. Phang Sock Yong, an economics professor at Singapore Management University. When the ALS debuted in 1975, it marked a revolutionary step in urban traffic management. In 1998, the ALS evolved into the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) system — the world's first automated system for managing traffic flow during peak hours.

Globally, from Jakarta to New York, cities in need of relief from severe congestion are looking towards Singapore as a blueprint. Dr. David Banks, a lecturer at the State University of New York at Albany, notes that nearly all reports regarding New York City's congestion pricing reference Singapore’s success story as a benchmark.

The Science Behind ERP

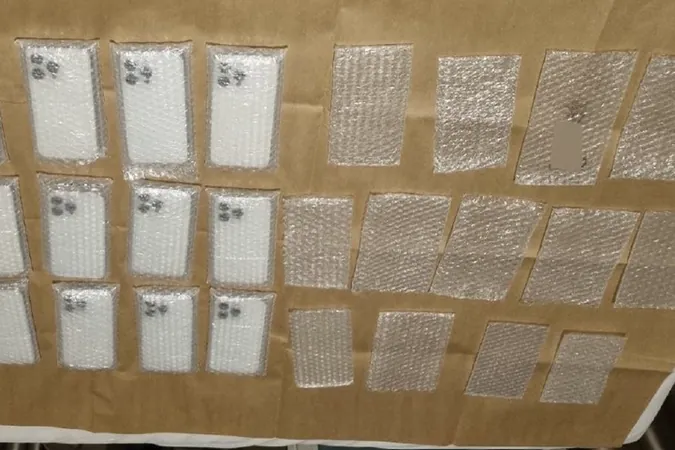

Unlike traditional traffic management solutions, which often merely penalize poor driving behaviors, the ERP system integrates advanced technology to track and manage road usage. It utilizes gantries equipped with short-range communication systems and cameras to charge drivers accurately during peak hours, thereby encouraging alternative routes or public transport.

Dr. Raymond Ong, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore, explains, "If done correctly, congestion pricing can significantly increase a roadway’s capacity." The idea hinges on the fact that reducing the number of cars on the road allows those that remain to travel faster, effectively enhancing overall traffic flow.

Besides alleviating congestion, Singapore's ERP system fosters environmental sustainability by reducing vehicle emissions and promoting pedestrian-friendly urban spaces.

Global Resistance While Singapore Thrives

Despite its effectiveness, congestion pricing schemes often incite public outrage. New York City recently attempted to implement a similar policy, facing substantial backlash and political pressure from various stakeholders, including U.S. President Donald Trump, who expressed intentions to roll back the initiative. Critics argue that such measures disproportionately affect lower-income drivers, calling for improved public transport systems.

Yet, many New Yorkers have come to appreciate the toll, with the latest polls revealing that a significant percentage support its continuation, largely due to the visible results in reduced traffic congestion.

Meanwhile, cities like London and Stockholm have shown how political determination and the right public sentiment can lead to successful congestion pricing systems. For instance, Stockholm’s approach, which also follows a cordon-based system, initially faced skepticism, but public opinion shifted positively after a trial period demonstrating reduced congestion.

Looking Ahead: ERP 2.0

As Singapore navigates its next phase of traffic management, the ERP is set to evolve once more with the introduction of ERP 2.0, based on GPS technology. This updated system promises more precise tracking, facilitating better data-driven decisions about road usage and congestion management.

In the wake of COVID-19, travel patterns in Singapore have changed, with a reported 6% decrease in overall traffic from the pre-pandemic period. With many ERP gantries remaining unactivated during this transition, experts are exploring additional strategies to reduce reliance on personal vehicles while enhancing public transport options.

Conclusion

Singapore's ERP system serves as an exemplary model for urban centers worldwide grappling with traffic congestion. As more cities consider adopting similar measures, the lessons learned from Singapore's unique challenges and solutions continue to inform global discussions around effective traffic management.

The future of urban mobility may very well depend on such innovative solutions where technology, public transport, and government will align to create a more sustainable and livable urban environment for all.

This article is part of a series exploring Singapore's innovative solutions to global challenges, showcasing how a small city-state can lead the way in transformative urban policy.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)