The Alarming Spread of Avian Flu: New Bird Species as Carriers Threaten Global Health

2025-03-25

Author: John Tan

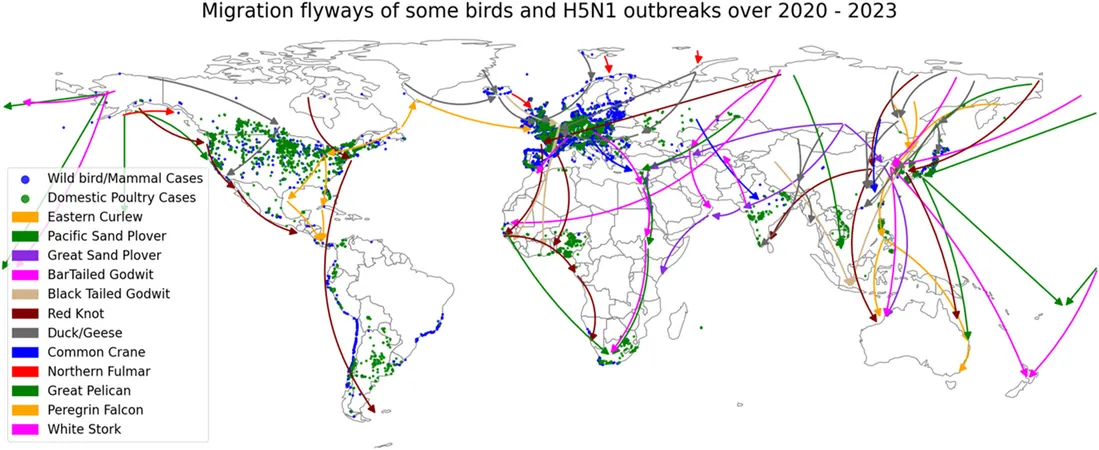

Avian flu cases are on the rise in the U.S. and worldwide, raising urgent concerns among health and wildlife experts. A groundbreaking study has identified how the virus has dispersed across continents over the past two decades, pinpointing a variety of new bird species—from pelicans to peregrine falcons—as carriers of this dangerous pathogen. The researchers suggest that this shift may explain why traditional methods, such as culling domestic birds, have failed to contain the latest outbreak.

As highlighted by a new study, wild birds are playing a dual role in the outbreak as both victims and vectors of the H5N1 strain of avian influenza. This shifts the previous understanding of avian flu transmission, prompting a call for updated monitoring and treatment practices for both wild and domestic birds to protect public health effectively.

The study emphasizes a dramatic change in the geography and timing of avian flu outbreaks, with the current hotspots spreading from Southeast Asia, where the virus was once concentrated, to Europe and the Americas. "We know H5N1 has the potential to become a human pandemic, and the risk of that happening is higher than ever," warns Raina MacIntyre, an epidemiologist from the University of New South Wales and a co-author of the study. With over thirty years of experience studying influenza, she urges for a comprehensive understanding of the disease's transmission dynamics to mitigate the associated risks.

Researchers utilized geospatial analysis and machine learning tools to track the H5N1 virus from its origins in 1997 up until 2023. Their findings present the first extensive evaluation of the avian flu's recent spread, revealing how shifts in species and migratory patterns contribute to the virus's persistence and expansion.

Birds utilize extensive migratory pathways known as flyways, critical for their survival as they crisscross the globe, often mixing with domestic poultry at rest stops. Unfortunately, these interactions provide favorable opportunities for the H5N1 virus to evolve and spread. While ducks, geese, and swans have historically been recognized as primary carriers, this study illustrates that a much broader range of bird species—including cormorants, pelicans, buzzards, vultures, hawks, and peregrine falcons—are now implicated in the transmission of avian flu.

The first major H5N1 outbreak was recorded in Hong Kong in 1997, where human infections and fatalities were tied to contact with infected chickens. Subsequent outbreaks in the following years, including those in 2005 and 2014-2015, demonstrated the virus's ability to leap across borders, infiltrating numerous countries. As of today, the outbreak that began in 2020 shows no signs of abating, even with control measures like culling.

"Our understanding must evolve beyond focusing solely on ducks, geese, and swans," warns MacIntyre. As monitoring wild birds on a global scale remains challenging, she stresses the importance of managing domestic bird populations as a crucial means of controlling outbreaks. For instance, free-range poultry, with greater exposure to wild birds, necessitate heightened biosecurity measures.

Pigs also pose a unique risk, serving as potential mixing vessels for viruses, particularly those in proximity to poultry. History has shown that successful collaborations and collective action can yield results in disease management, and thus, MacIntyre emphasizes that tackling this global problem requires equally global solutions.

As we face an unprecedented rise in avian flu cases, understanding and re-evaluating our approach to monitoring both wild and domestic birds is essential to safeguard human health and mitigate the bewildering risks posed by this evolving virus.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)