Surprising Discovery: Uranus' Tiny Moon Miranda Might Harbor a Hidden Ocean!

2024-10-29

Author: Daniel

Introduction

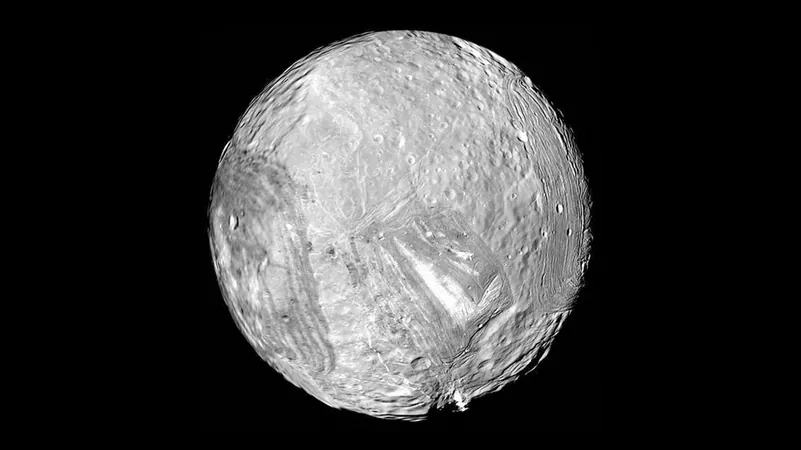

Reports suggest that the many moons of our Solar System resemble a vast jigsaw puzzle, revealing not only their physical characteristics but also the complex processes that have sculpted them. Among these celestial bodies is Miranda, the smallest of Uranus' 28 known moons, measuring just 471 kilometers in diameter. Recent research has unveiled a possibility that might change the narrative surrounding this icy moon: it may be concealing a subsurface ocean.

Miranda's Unique Features

Miranda is unique among Uranus' moons due to its strikingly chaotic surface, characterized by a blend of jagged terrain, scattered craters, steep cliffs, and mysterious grooves. Among its fascinating features is Verona Rupes, which could be the tallest cliff in our Solar System at an astonishing height of 20 kilometers. Scientists speculate that tidal heating—stemming from gravitational interactions with Uranus' other moons—may account for Miranda’s intriguing geological composition.

Groundbreaking Research

A groundbreaking study published in The Planetary Journal, titled "Constraining Ocean and Ice Shell Thickness on Miranda from Surface Geological Structures and Stress Modeling,” brings fresh understanding to its geology. The research, led by Caleb Strom from the University of North Dakota, indicates that there may be more to Miranda than previously recognized.

Historical Context

With only a brief encounter from Voyager 2 in 1986 providing data on Miranda’s southern hemisphere, scientists have long grappled with the moon's enigmatic surface. The spacecraft’s images sparked intrigue, leading some to label Miranda as a "patchwork planet." Though the data was sparse, researchers now have the advantage of advanced computer simulations to explore Miranda’s hidden secrets.

Modeling and Findings

Utilizing sophisticated modeling techniques, Strom and his colleagues began by cataloging the moon’s surface features—ridges, cracks, and unique trapezoidal areas—and then reverse-engineered those to assess possible internal conditions. The results from their analyses support the theory that Miranda may have possessed a vast ocean beneath its surface between 100 to 500 million years ago. The findings suggest that the icy crust might be less than 30 kilometers thick, while the underlying ocean could reach depths of up to 100 kilometers.

Scientific Perspectives

Remarkably, Tom Nordheim, a co-author of the study and a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), expressed his astonishment at discovering the potential for a hidden ocean in such a small moon. He stated, "This discovery enhances the intrigue surrounding the moons of Uranus, indicating several may be ocean worlds hiding in plain sight."

Role of Tidal Heating

The hypothesis of tidal heating—caused by gravitational tugs among Uranus' moons—plays a critical role in this discovery. These moons experience orbital resonances that amplify gravitational interactions, leading to periodic deformation and heat generation, which may allow subsurface oceans to remain warm and liquid.

Orbital Changes

In the past, it is believed that Miranda was in a state of orbital resonance with other moons, potentially causing its current fractured landscape. However, the researchers theorize that it has since exited this resonant state and begun to cool. The ocean, they propose, is likely still present but thinner than it once was. Surprisingly, the moon may not fully be frozen; otherwise, the expansion of a completely solidified ocean would have resulted in distinct surface cracks.

Comparison with Enceladus

This revelation is reminiscent of past misconceptions about Saturn's moon, Enceladus. Once thought to be a rigid ice mass, subsequent investigations via the Cassini mission unveiled a dynamic world with a warm subsurface ocean. Today, researchers speculate about similar possibilities for Miranda.

Further Investigations

Given the physical similarities between Miranda and Enceladus, both of which boast ice shells and comparable sizes, the prospect of a subsurface ocean in Miranda becomes increasingly plausible. Scientists are now ramping up their efforts to investigate these distant moons within our solar system, especially as Jupiter’s Europa remains a prime target in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Conclusion and Future Missions

Exciting new studies indicate that Miranda may not be as geologically dormant as previously thought. Emerging data suggests Miranda could be venting material into space, much like Enceladus. With ongoing missions targeting ocean worlds like Europa, there’s a compelling argument for including Uranus and its moon Miranda in future exploratory endeavors.

Yet, without further empirical investigation, the reality of an ocean lying beneath Miranda's surface remains uncertain. As Nordheim emphasizes, "We are maximizing the scientific yield from the Voyager 2’s legacy images, but we are eager for a dedicated mission back to Uranus to unveil more about its intriguing ocean moons."

Final Thoughts

In summary, the research proposes that Miranda might have once housed a subsurface ocean, influenced by tidal stresses and heating events, suggesting an intense geologic history. With tantalizing possibilities emerging, this little moon at the edge of our solar system may hold secrets that could revolutionize our understanding of ocean worlds. What other surprises await in the cold depths of the cosmos? Only time—and more exploration—will tell!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)