Shocking Study Reveals Why 'Lucy', Our Ancient Ancestor, Was a Terrible Runner!

2024-12-26

Author: Ming

Introduction

A groundbreaking study on "Lucy," our 3.2 million-year-old hominin relative, has unveiled that she was far from a swift runner! This new research peels back the layers of her anatomy, shedding light on the evolutionary developments crucial to efficient running in humans today.

The Evolution of Bipedalism

Believe it or not, the ability for humans to walk and run seamlessly on two legs didn't emerge until around 2 million years ago with our distant relatives, Homo erectus. Before that, the australopithecines, such as Australopithecus afarensis (which Lucy belongs to), were already bipedal as far back as 4 million years ago. However, their body proportions—with long arms and shorter legs—led scientists to presume that these early humans were significantly less adept at running than we are today.

New Research Findings

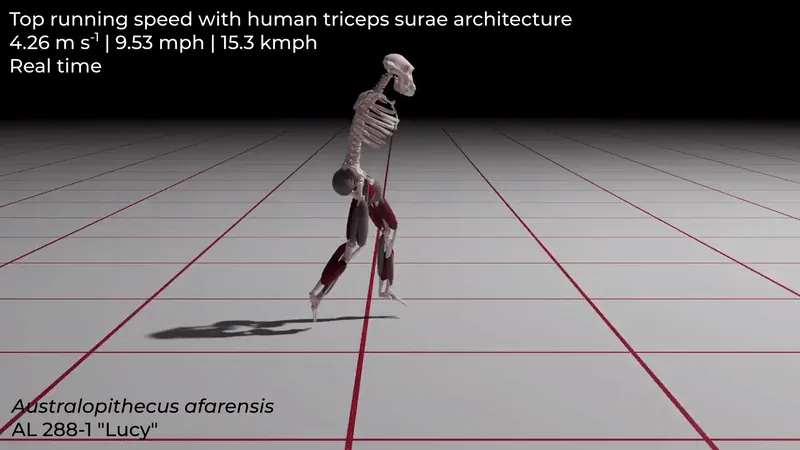

A study recently published in *Current Biology* models Lucy's skeletal and muscular structure to estimate her maximum running speed, endurance, and the energy expenditure during her runs. The results? Lucy's maximum running speed was alarmingly low, hitting just about 11 mph (18 km/h). To put this into perspective, sprinting superstar Usain Bolt reaches speeds over 27 mph (43 km/h), while the average recreational runner tops out around 13.5 mph (22 km/h). To add to this, Lucy used between 1.7 and 2.9 times more energy to achieve her maximum speed compared to modern humans, hinting that she needed far more energy than contemporary runners to cover the same distance.

Anatomical Insights

The anatomical features of australopithecines, including their bulky upper bodies and short legs, were likely significant contributors to their reduced speed. But the startling revelation surfaced when researchers identified the unique design of Lucy’s Achilles tendon and the triceps surae muscles in her calves as additional culprits behind her lackluster performance on the track.

Comparison with Modern Humans

Modern humans boast a long, elastic Achilles tendon connecting the calf and ankle muscles to the heel, providing the powerful push needed for sprinting. When the researchers modified Lucy’s movement model to adopt a more human-like Achilles tendon and calf muscles, her speed did improve slightly—but she still lagged behind, primarily due to her smaller frame.

Conclusion and Future Research

This study is the first to have utilized musculoskeletal modeling to estimate running capability specifically in Lucy's species, marking a major advancement in our understanding. However, the researchers remind us that further investigations are required, incorporating parameters such as arm swing and torso rotation. This additional modeling could illuminate the substantial differences in locomotion techniques between australopithecines and modern humans.

Implications of the Findings

The findings underscore how particular adaptations in human anatomy have evolved specifically for enhanced running—and just how much our ancient ancestors struggled in areas where we now excel. What other secrets are waiting to be uncovered about Lucy and her kin? Stay tuned, as this fascinating journey into human evolution continues!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)