Shocking New Research Links Cytomegalovirus to Alzheimer’s Disease: Is Your Gut Health at Stake?

2024-12-20

Author: Mei

Groundbreaking Study Overview

A groundbreaking study from Arizona State University (ASU) and the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute has revealed a surprising link between cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a virus that commonly lingers in the gut, and a specific subtype of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This revelation could have significant implications for millions of individuals. The findings are freshly published in the journal *Alzheimer's & Dementia*.

Key Findings

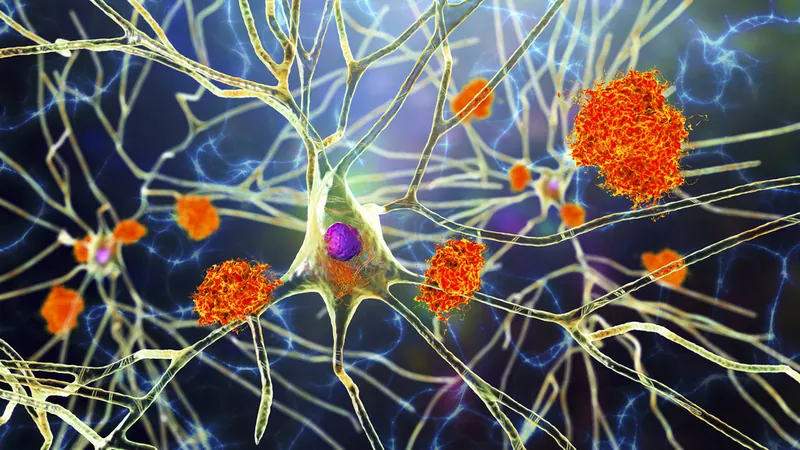

Dr. Ben Redhead, co-first author and a prominent professor at the ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center, stated, “We believe we've identified a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that could affect between 25% and 45% of those diagnosed with the disease.” This subtype not only shows the classic signs of Alzheimer's—such as amyloid plaques and tau tangles—but also exhibits a distinct biological profile characterized by specific viruses, antibodies, and immune cells in the brain.

Role of HCMV

HCMV is widely contracted early in life, with most individuals exposed by their third decade. While the virus usually stays dormant, in some it may reactivate, residing actively in the gut and potentially traveling to the brain through the vagus nerve. Once there, HCMV can provoke the brain’s immune cells, known as microglia, to express a gene called CD83. This gene plays a crucial role in the brain's immune response, and its activation is associated with inflammation and neuronal damage—two key features of Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous Research

Earlier studies published in *Nature Communications* suggested that postmortem brains of AD patients exhibited higher levels of CD83(+) microglia compared to those without the illness. Further exploration revealed antibodies in the intestines of AD patients, implying that some sort of infection could be implicated in their condition. The new research has established a direct connection linking CD83(+) microglia to the presence of HCMV antibodies found both in the intestines and cerebrospinal fluid of affected individuals. Additionally, researchers confirmed HCMV in the vagus nerve, suggesting this pathway could be a route for the virus to access the brain.

Population Statistics

While a majority of the population—about 80% by age 80—shows signs of HCMV exposure, the study notes that only a subset of individuals have detectable HCMV in their intestines. This means that the presence of these antibodies is crucial to understanding how the virus interacts with the brain.

Implications for Future Research

These exciting findings illustrate the complex interplay between viruses and brain health, paving the way for future research aimed at clarifying the role HCMV plays in Alzheimer’s pathology. To further this line of inquiry, the ASU-Banner team is working on developing a blood test to identify chronic intestinal HCMV infections in patients. This test could enhance our understanding of this Alzheimer’s subgroup and evaluate whether existing antiviral medications might play a role in treating or preventing this form of the disease.

Conclusion

Could this be the key to unlocking new treatments for Alzheimer’s? Stay tuned as this research unfolds!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)