Shocking Discovery: How Antibiotics May Trigger Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

2024-09-15

Introduction

Recent research has unveiled a troubling connection between antibiotic use and an increased risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), affecting millions worldwide. As of 2019, approximately 4.9 million people were living with this chronic condition, which primarily manifests as two forms: Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Despite extensive studies, the exact cause of IBD remains a mystery, with no known cure available.

Research Findings

A team of researchers at Bar-Ilan University in Israel has conducted groundbreaking studies that suggest antibiotics might not only attack harmful bacteria but may also have detrimental effects on the protective mucus layer of the gut, potentially heightening the risk of IBD. Published in Science Advances, the research utilized an advanced mouse model to explore this alarming potential.

Dr. Shai Bel, the principal investigator and lead author of the study, pointed out that prior epidemiological studies have indicated a significant correlation between antibiotic usage and IBD development, which seems to increase with the amount of antibiotics consumed. "Unlike many other environmental factors, this is one that can be tested in the lab in a well-controlled fashion," he stated.

Research Methodology

During the study, researchers employed techniques such as RNA sequencing and machine learning to closely observe the consequences of administering various antibiotics, including ampicillin, metronidazole, neomycin, and vancomycin. The findings were startling: these antibiotics compromised the gut's protective mucus layer, permitting bacteria to infiltrate and potentially intensifying inflammation within the gut—an early warning sign for conditions like IBD.

Unexpected Discoveries

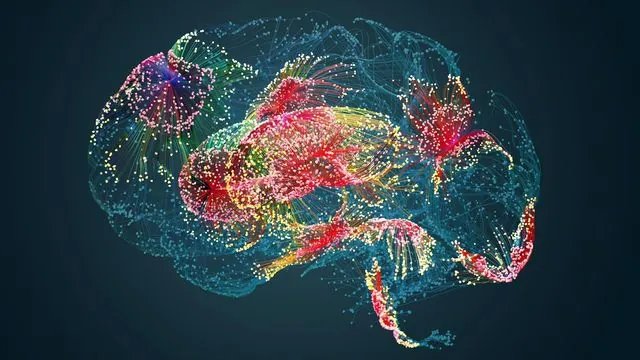

"We always thought that antibiotics harm only bacteria and not us, but our new research has found that antibiotics directly affect the cells in our intestine," Dr. Bel explained. He expressed that this discovery contradicts the long-held assumption in both medicine and agriculture that antibiotics solely impact bacterial cells.

What’s even more surprising is that the adverse impact on the mucus barrier was determined to be linked not to changes in gut microbiota, but instead to alterations in the intestinal wall cells responsible for mucus production. This revelation suggests that antibiotics could provoke undesirable immune responses that lead to IBD, rather than merely disrupting gut flora.

Implications of the Findings

The implications of these findings are monumental. "Antibiotics should absolutely be used when needed, but there has been an alarming trend of over-prescription," Dr. Bel cautioned. "Perhaps with this new knowledge, antibiotic use can be limited to cases where it is demonstrably beneficial."

Medical experts, including pediatric gastroenterologist Dr. Harpreet Pall, have noted the significance of this study, emphasizing that it changes our understanding of how antibiotics affect gut health. "By better understanding the risk factors for IBD, researchers can develop prevention strategies and personalized treatments," Dr. Pall added, advocating for further research into other factors that may interact with antibiotic use in IBD patients.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Dr. Ashkan Farhadi, a board-certified gastroenterologist, remarked that the study’s outcomes were "a bit shocking," reshaping long-held beliefs about the mechanisms behind both antibiotics and IBD. While some earlier reports linked antibiotic use to IBD, the distinct mechanism unveiled in this study emphasizes how antibiotics may alter human cells rather than just the gut microbiome—which marks a pivotal shift in thinking.

As research continues, it becomes increasingly crucial to reconsider the role of antibiotics in our health care practices. With potential new treatment avenues on the horizon, the scientific community remains eager to explore how to mitigate IBD risk while ensuring effective antibiotic use. Exciting developments could emerge from disease prevention strategies rooted in this newfound understanding of how antibiotics interact with our bodies.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)