Revolutionary Discovery: How a Sugar Molecule on Antibodies Could Change Your Fight Against Influenza!

2024-11-13

Author: Yu

Revolutionary Discovery: How a Sugar Molecule on Antibodies Could Change Your Fight Against Influenza!

Viruses are known to be the fastest-evolving organisms on our planet, which is a significant reason why we find ourselves getting flu shots every year. Just when we think we’ve developed immunity against a strain, seasonal influenza manages to outsmart us, leading to annual infections and, at times, even pandemics. Notably, the 1918 flu pandemic devastated the globe, claiming about 50 million lives and infecting one-fifth of the world's population—a stark reminder of the virus's lethal potential, reinforced by outbreaks in 1957, 1968, and 2009.

Dr. Taia Wang, an associate professor at Stanford Medicine specializing in infectious diseases, emphasizes the ongoing danger of influenza. “Influenza remains an incredibly dangerous risk to global health,” she states, underscoring the urgent need for innovative approaches to combat this virus.

The Link Between Sialic Acid and Flu Severity

A groundbreaking study led by Wang and her colleagues has unveiled a striking discovery: the relative abundance of a specific sugar molecule known as sialic acid on our antibodies plays an unexpectedly powerful role in determining the severity of flu infections. This newfound insight not only aids our understanding of influenza but also opens doors for potential therapies that could vastly improve outcomes in severe cases.

The research, recently published in the journal *Immunity*, reveals that the presence of sialic acid on antibodies can differentiate between mild and severe flu cases. Those with higher levels of this molecule exhibited milder symptoms compared to those whose antibodies had lower sialic acid content. This finding was further corroborated in bioengineered mice that were given human antibodies with varying sialic acid levels. The results were astounding: mice treated with sialic acid-rich antibodies displayed significantly less severe symptoms, highlighting the molecule's crucial protective effect—even when infected by different flu subtypes.

How It Works: Taming the Inflammatory Response

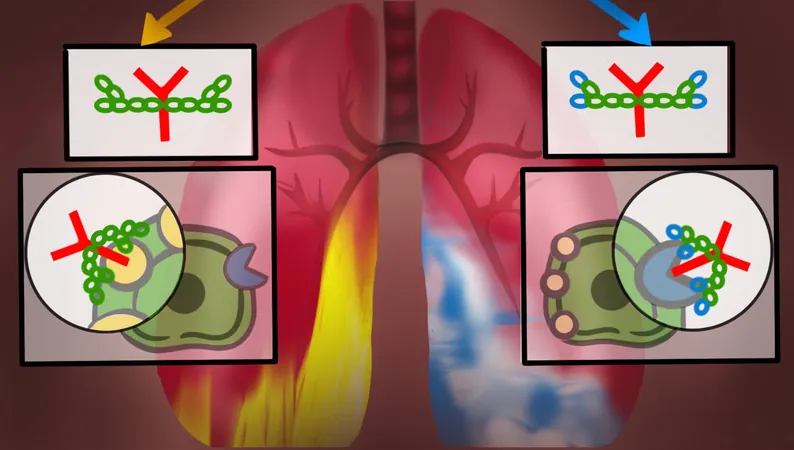

The protective mechanism revolves around a receptor in our immune cells known as CD209. Wang's team discovered that antibodies with higher sialic acid content bind to CD209, which then reduces inflammation during a flu infection. This is particularly important, as severe cases are often driven not by the virus itself but by a runaway inflammatory response that leads to extensive lung damage and compromised respiratory function.

In fact, their findings suggest that managing inflammation could provide a new pathway for protecting against severe influenza, potentially applicable to other infectious diseases as well. Wang stated, “We've discovered a new way to protect against severe influenza by shutting down this follow-on inflammation, regardless of ongoing viral replication.”

A Boon for Vulnerable Populations

One of the most fascinating implications of this research relates to the elderly. Older individuals generally have lower levels of sialic acid in their antibodies, which may explain their heightened susceptibility to severe flus and other chronic diseases. Wang points out that this decline in sialic acid correlates with increased levels of chronic inflammation that plague older populations, potentially leading to conditions like heart disease, Alzheimer's, and cancer.

Future Directions: Expanding the Research Horizon

The implications of these findings are profound. The antibody "stalks" enriched with sialic acid, currently being investigated for their efficacy in treating autoimmune disorders, could lead to breakthroughs not just for influenza, but for a wide array of inflammatory diseases. Wang’s team is already embarking on longitudinal studies to explore whether these enriched antibody stalks can predict disease progression in flu patients, potentially revolutionizing how we approach flu treatment and prevention.

As Wang continues her research, she highlights a critical reminder: “Age is a major factor that differentiates people based on sialic acid abundance in antibodies. Understanding this relationship could be key in addressing various age-related health issues.”

In conclusion, this discovery could redefine our strategies against influenza and other infectious diseases, providing a new beacon of hope in public health, particularly for our vulnerable elderly populations. Keep an eye on this developing research, as it may soon change the way we think about immunity in the age of rapidly evolving viruses!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)