Did NASA's 1970s Mars Mission Unintentionally Snuff Out Martian Life? A Controversial Theory Emerges!

2024-11-16

Author: Siti

In a startling revelation, astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch from the Technische Universität Berlin has proposed a shocking theory: that humanity may have inadvertently extinguished life on Mars during NASA's Viking 1 mission in the 1970s.

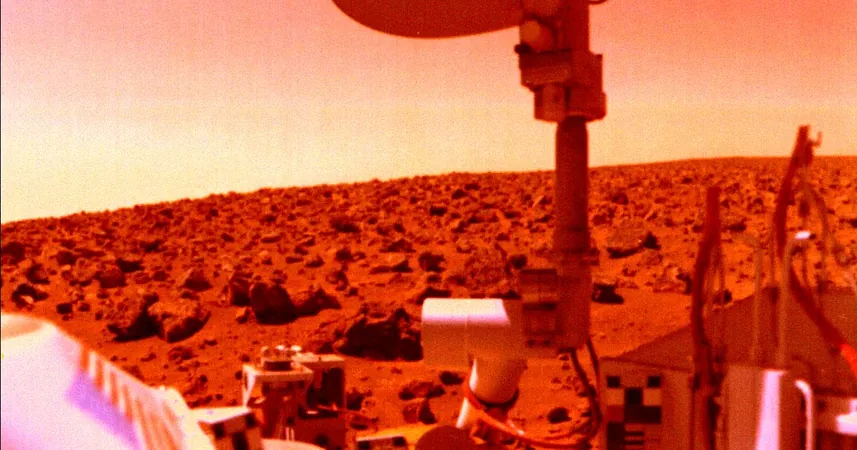

The Viking 1 mission, which landed on the Red Planet in 1976, was a groundbreaking endeavor that involved two spacecraft conducting experiments by mixing water and nutrients with samples taken from Martian soil. At that time, researchers operated under the assumption that if life existed on Mars, it would require liquid water similar to life on Earth.

Early results from these experiments hinted at the tantalizing possibility of life, igniting decades of discussions and debates among scientists. However, subsequent evaluations led many to conclude that these initial signs were indeed false positives.

Schulze-Makuch suggests that instead of finding life, the Viking landers may have accidentally killed it. His reasoning hinges on the idea that Martian life could be dependent on salt deposits for water—a survival method akin to that used by extremophiles in Earth's driest regions, such as the microbes of Chile's Atacama Desert.

“In hyperarid environments, life can extract moisture from salts that absorb water vapor from the atmosphere,” Schulze-Makuch stated in a commentary for the prestigious journal Nature. “This suggests that future Mars missions should focus on searching for salts, rather than just following the traditional ‘water’ strategy.”

Schulze-Makuch argues that the water-based experiments conducted by the Viking landers may have applied excessive moisture, thereby killing any latent life forms they might have encountered. This assertion challenges the long-held belief that liquid water is essential for life to survive.

Furthermore, he posits that substances such as sodium chloride (the primary salt on Mars) could create a brine similar to conditions where certain bacteria thrive on Earth—a concept he believes could be applicable to life on Mars as well. He referenced a significant study indicating that torrential rains had devastated up to 80% of indigenous bacteria in the Atacama Desert due to their inability to cope with the sudden influx of water.

Nearly 50 years post-Viking mission, Schulze-Makuch calls for renewed efforts to detect life on Mars, suggesting that advances in our understanding of the Martian environment make this an opportune moment for a new life detection mission.

But with these ideas still hovering in the realm of theory, Schulze-Makuch emphasizes the need for diverse and independent life-detection techniques. “We must adopt a multifaceted approach to detection that can provide us with more compelling evidence,” he concluded.

As the debate on the existence of life on Mars gains new traction, this provocative theory invites further inquiry and exploration—could the remnants of Martian life still be hidden in the salty depths of the Red Planet, waiting for a new wave of scientific discovery to bring them to light?

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)