Breakthrough Method Sheds Light on Contaminant Build-Up in Arctic Marine Life Amid Climate Change

2025-03-17

Author: Daniel

Introduction

A groundbreaking approach to tracking the dietary habits and contaminant exposure of Arctic marine mammals is providing essential insights as climate change drastically alters the region's food web.

Research Methodology

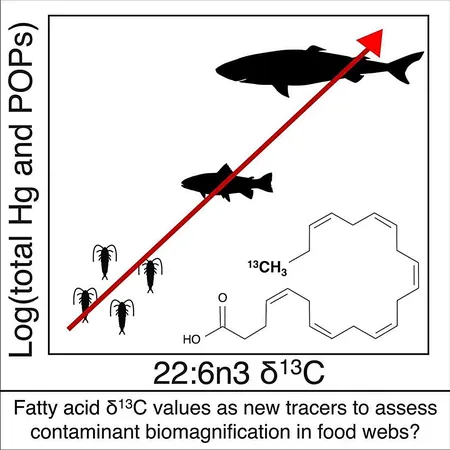

Led by Adam Pedersen, a newly minted Ph.D. graduate from McGill University's Department of Natural Resource Sciences, a team of researchers has developed a methodology that utilizes carbon isotopes of fatty acids. This innovative technique enhances our understanding of what migratory species like killer whales and top Arctic predators such as polar bears consume and how they accumulate hazardous contaminants.

“Our approach effectively addresses significant limitations of traditional methods,” stated Pedersen, the principal author of the study. “It is particularly valuable for species like killer whales, whose diets change as they migrate northward. Grasping these dietary shifts is vital in the context of escalating climate change.”

Significance of Findings

Published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, the findings present a higher-resolution alternative to conventional bulk stable isotopes. This traditional method proves insufficient when studying species that traverse vast areas with varying ecosystems.

As temperatures in the Arctic continue to rise, killer whales are venturing farther into the region, often encountering new prey, including other marine mammals. Unlike the typical fish-based diet they rely on in the North Atlantic, these marine mammals, which include seals, reside at a higher trophic level in the food chain and harbor significantly more contaminants.

Similarly, as the Arctic's sea ice diminishes, polar bears may be shifting their diets towards these more contaminated seals. Pedersen's research indicates that their new method can more effectively track these dietary changes and the accumulation of contaminants within food webs compared to traditional techniques. Notably, these dietary shifts may lead to alarming increases in contaminant levels in killer whales and polar bears—posing dire risks not only for the animals themselves but also for human populations that might consume them.

Ecological Implications

Moreover, through their waste, post-mortem decay, or by being eaten by humans, contaminated killer whales and polar bears may inadvertently distribute pollutants back into the environment, wreaking havoc on other species and throwing off the ecological balance.

“These contaminants biomagnify up the food chain, meaning marine mammals—and subsequently their predators—can accumulate levels of harmful substances orders of magnitude greater than those found in fish,” explained Pedersen. “Our method sheds light on the dynamics of contaminant accumulation, which is crucial for effective conservation efforts.”

A Tool for Conservation and Policy Development

To develop this new technique, Pedersen and his team analyzed small blubber samples collected from whales harvested by Indigenous subsistence hunters in Greenland. They employed gas chromatography, a technique for separating and analyzing components within a mixture, along with isotope ratio mass spectrometry to detect the carbon isotopes of the separated compounds. By extracting and evaluating fatty acids, the researchers successfully reconstructed dietary patterns, which were then used to interpret variations in contaminants throughout the food web. These high-resolution insights have the potential to shape policies aimed at mitigating contaminant exposure in Arctic ecosystems.

“This research holds tremendous promise for informing contaminant management practices,” stated Melissa McKinney, an Associate Professor of Natural Resource Sciences, Canada Research Chair in Ecological Change and Environmental Stressors, and Pedersen's Ph.D. supervisor. “By enhancing our comprehension of how contaminants accumulate through food webs to significant levels in apex predators, we can better anticipate contaminant dynamics in a changing climate.”

Future Directions and Collaboration

Despite the exciting findings, Pedersen cautioned that further validation is necessary. “This method has only been applied within a single food web to date,” he noted. “More comprehensive studies are essential to validate its wider applicability. However, the initial results are thrilling and may inspire other researchers to embrace this innovative approach.”

Importantly, the researchers underscore the need for real-world sample collection, achieved in collaboration with local Indigenous communities.

“Partnering with Indigenous hunters enabled us to gather crucial data without disrupting the natural ecosystem,” Pedersen remarked.

Conclusion

This pioneering research could pave the way for enhanced understanding and preservation of Arctic marine life, ultimately protecting the delicate balance of these ecosystems in the face of advancing climate change.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)