Are Small Effects Significantly Impactful for Vulnerable Populations? Insights from the ECHO Study

2024-09-28

Author: Nur

Are Small Effects Significantly Impactful for Vulnerable Populations? Insights from the ECHO Study

Epidemiological research constantly grapples with a pivotal question: Are the observed effects of environmental exposures substantial enough to matter in clinical or public health contexts? A common method to assess this involves comparing mean health outcomes between exposed and unexposed groups. However, translating these differences into clinically meaningful interpretations remains a challenge.

Researchers often lean on minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) or utilize Cohen's standardized effect size ‘d’ (calculated as the difference in means divided by the standard deviation). An effect size of 0.8 is termed ‘large,’ 0.5 is ‘medium,’ and 0.2 is considered ‘small.’ Yet, even reputable papers often misinterpret p-values as measures of effect size, leading to misconstrued conclusions about the significance or relevance of findings.

A compelling alternative is to examine whether a known threshold for a continuous health outcome can identify individuals at a ‘high risk’ of adverse outcomes. For instance, the World Health Organization defines low birthweight as a weight of less than 2500 grams, a crucial standard for evaluating outcomes like perinatal health.

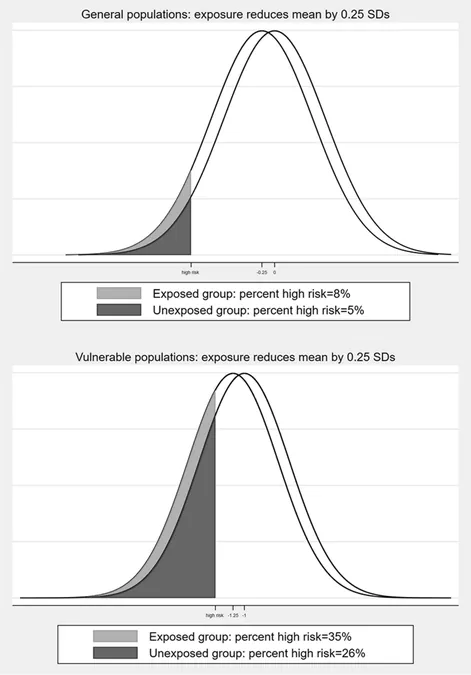

In looking specifically at vulnerable populations, it becomes evident that the impact of even minor exposure effects can be magnified. Consider a small change in birthweight among full-term versus preterm infants: the risk of low birthweight is inherently higher in preterm births. Therefore, a slight reduction in mean birthweight can significantly increase the number of infants at high risk. These small shifts can easily go unnoticed in broad statistical analyses, particularly due to inadequate statistical power.

The Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program provides critical insights. Launched by the National Institutes of Health in 2016, ECHO aims to explore the effects of various environmental exposures on child health outcomes. The first cycle, running from 2016 to 2023, encompasses a diverse set of 69 cohorts across 31 consortia, representing over 43,000 pregnancies and children throughout the United States.

This research utilizes data from the ECHO program to model how minor differences in health outcomes, such as birth weight, affect vulnerable populations. By focusing on factors like maternal education, health insurance status, race, and ethnicity, the study illustrates how these social determinants correlate with health disparities.

Findings reveal alarming trends: mean birthweights and the percentage of low birthweight children exhibit stark variations based on socioeconomic factors. For instance, Black mothers recorded a staggering 13.5% low birthweight rate compared to 5.9% for White mothers. Additionally, the study highlights that even small reductions in mean birthweight—hypothetically decreased by 50 grams—lead to a disproportionately larger increase in the percentage of low birthweight infants among vulnerable subpopulations.

As the effect size increases from minor to more substantial (125g, 167g, up to 250g reductions in birthweight), the disparities only grow more pronounced. Black children, for instance, exhibit a risk difference that far exceeds that of their White counterparts, thereby underscoring compounded health risks among already vulnerable groups.

The study underscores a vital point for public health: a small detrimental change in environmental factors can translate to significant implications for high-risk communities. This correlation between exposure magnitude and population vulnerability emphasizes the necessity for detailed analyses that account for sociodemographic disparities.

A crucial takeaway is that seemingly small effects can carry significant weight in the context of public health, especially for vulnerable populations. The ECHO study's findings highlight the importance of integrating sociocultural dimensions into health assessments and risk evaluations. Future studies should prioritize stratifying data by these factors to accurately capture the full scope of health disparities and sculpt interventions that genuinely address the needs of at-risk groups.

By recognizing these nuances, public and environmental health policies can better support vulnerable populations, pointing to the fact that even the smallest changes can lead to substantial differences in health outcomes. The work of ECHO sets a crucial precedent and calls for a deeper understanding of the interplay between environmental factors and health inequities that persist across various populations.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)