Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science: NMSU Researchers Uncover the Power of Rancid Animal Fats as Insect Repellents

2024-10-28

Author: Arjun

Introduction

In a fascinating intersection of history and biology, researchers at New Mexico State University (NMSU) have revitalized ancient insect repellent techniques used by Native Americans, revealing the effectiveness of rancid animal fats. While most people wouldn’t even think of slathering rancid pig lard on their skin to ward off mosquitoes, studies show this unconventional approach may have merit.

Historical Context

Texas archaeologist Gus Costa collaborated with NMSU biology professor Immo Hansen’s lab to investigate historical accounts from Spanish conquistadors who documented the use of rancid fats by Native Americans as mosquito repellents in the Gulf Coast region during the 1700s. Given that this area is notorious for its mosquito populations, the practice likely held significant practical value.

Research Methodology

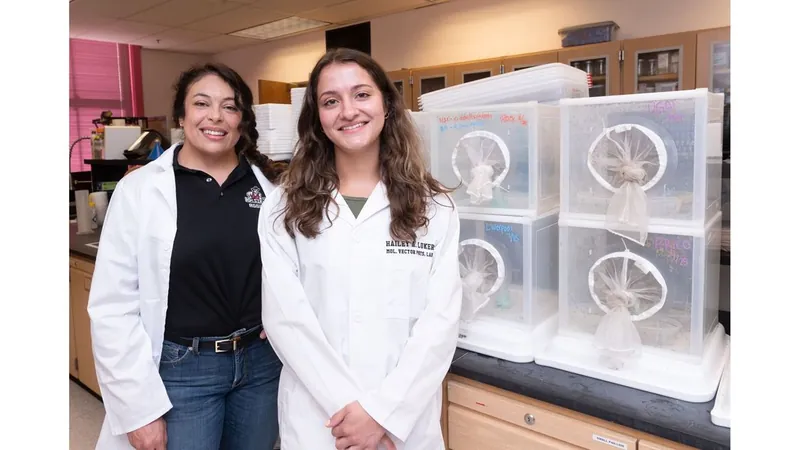

Over five years, Costa sourced various rancid fats—provided by researchers and procured from reliable sources—culminating in a comprehensive study finally published in PLOS ONE. Co-authors included Ph.D. candidate Hailey Luker and lab manager Claudia Galvan, alongside Hansen. Historically, few Native American mosquito repellent strategies have undergone controlled scientific testing. Hansen’s team sought to address this gap by analyzing multiple types of fats—ranging from alligator and cod to bear and pig lard—at different stages of rancidity. Environmentally conscious methods were prioritized, ensuring that each fat was sustainably sourced.

Findings on Rancidity

The researchers began their investigation by assessing rancidity levels based on odor using a rating scale from one (no smell) to five (strong smell). Interestingly, the study revealed that rancidity, rather than freshness, correlated with increased insect-repelling efficacy. This suggests that the fragrance produced from rancid fats could play a pivotal role in their effectiveness. "Though rancid doesn't always equate to unpleasant, it does signify a chemical transformation that enhances the repelling properties," Luker explained.

Testing Against Mosquitoes

The researchers used yellow fever mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) for their tests. They conducted assays measuring the duration of protection provided by the rancid fats on human skin and evaluated long-distance repellency using a Y-tube olfactometer. Remarkably, the study concluded that rancid fats from cod, bear, and alligator were effective against mosquitoes, though their repelling effects were short-lived.

Limitations and Future Research

Moreover, the study highlighted that neither rancid nor fresh fats showed effectiveness against ticks, sparking further curiosity for future research avenues. Hansen emphasized that the challenge now lies in identifying specific active ingredients responsible for repelling mosquitoes. "Our findings could pave the way for developing more effective, less odorous insect repellents," he noted.

Conclusion

This research not only validates the ethnohistorical knowledge of Native American practices but also shines a light on a wealth of traditional remedies that have stood the test of time. Galvan expressed a desire to enhance these natural methods in her future career at the CDC, making a compelling case for integrating ancient wisdom with contemporary solutions.

As the planet grapples with increasing mosquito-borne diseases, this study could herald a new era of eco-friendly and effective insect repellents that honor centuries-old practices while addressing modern public health needs.

Stay tuned as more discoveries emerge from this groundbreaking study, which blends tradition with science for a healthier future!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)