Why Does It Feel So Cold When Earth Is Closest to the Sun?

2025-01-04

Author: Kai

The Science Behind the Chill

Even as we orbit closer to the sun, winter’s icy grip remains relentless. Breath condenses in the crisp air, roads glaze over with ice, and the sun hangs low in a seemingly perpetual haze. The truth lies not in our proximity to the sun but in the angle at which Earth tilts on its axis. During January, the Northern Hemisphere tilts away, leading to the frigid temperatures and shorter days we experience.

In stark contrast, while we scrape ice off our windshields, folks in Sydney and Buenos Aires are basking in summer sunshine. The Southern Hemisphere enjoys longer days and warmer weather as it tilts towards the sun this time of year.

Understanding Perihelion

When we reach perihelion, Earth will be about 0.98333 astronomical units away, which translates to nearly 147 million kilometers (91 million miles) from the sun—approximately five million kilometers (around three million miles) closer than when we hit our farthest point, or aphelion, on July 3, 2025. It’s a fascinating reminder that our yearly cycles are dictated largely by these orbital mechanics.

All planets follow a similar elliptical path as they orbit stars, a discovery established in the 17th century by the brilliant German mathematician Johannes Kepler.

The Eccentric Orbit and Its Effects

While being closer to the sun during perihelion does cause a slight uptick in solar energy (about 7% more sunlight), that doesn’t automatically translate to warmer weather in January. The majority of the Southern Hemisphere is covered by vast oceans, which buffers the rise in temperatures, mitigating the anticipated effects of being nearer to the sun.

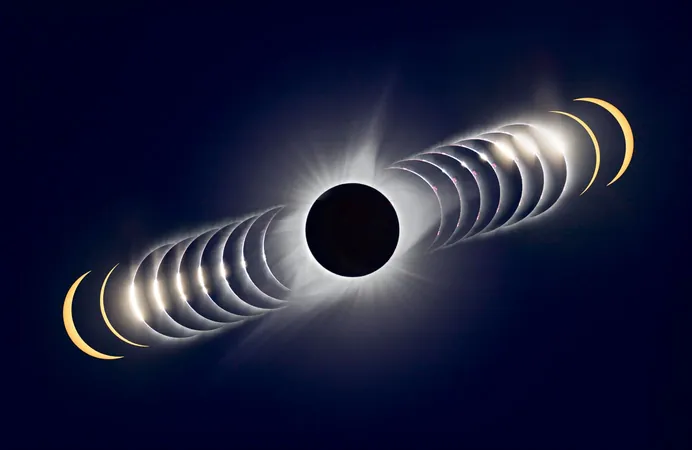

What Is the ‘Solar Maximum’ All About?

Currently, Earth is also experiencing a solar maximum, a phase in the sun’s 11-year cycle marked by heightened solar activity. This period is characterized by increased production of solar radiation and spectacular phenomena like vibrant Northern Lights.

During this solar maximum, the total energy received by Earth, measured as Total Solar Irradiance from satellites, rises by a mere 0.1%. Although this increase is often hailed as significant, it has little impact on our overall climate.

The Bottom Line

So next time you feel that biting cold, remember: Even when we’re closer to the sun, it’s all about the orientation of our planet and the geographical nuances of its different hemispheres. As January unfolds, let’s hope for clearer skies and warmer days ahead! Keep your winter jackets handy; you may need them for a while longer.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)