Warning Signs: 'Zombie Deer Disease' Threatens to Erupt into a Global Crisis!

2025-03-20

Author: Wei

Introduction

In a troubling development that stretches across the entire continental United States, a pattern of chronic wasting disease (CWD) infections is being reported in deer populations from coast to coast. This contagious neurodegenerative disorder affects various members of the cervid family, including deer, elk, moose, and even reindeer at higher latitudes. Alarmingly, there is currently no known vaccine or treatment for this disease, which is invariably fatal.

The Emergence of CWD

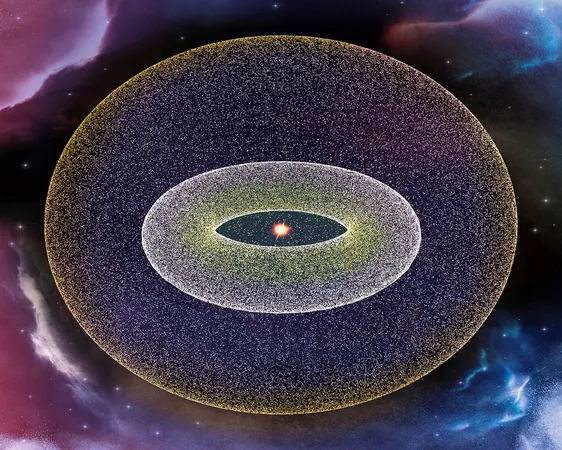

Scientists now describe CWD as a “slow-motion disaster in the making.” The infection quietly began to emerge in wild deer herds in Colorado and Wyoming as early as 1981. Fast forward to today, this devastating disease has now infiltrated wild and domestic game populations across 36 U.S. states, parts of Canada, and has even made its way to farmed deer and elk in South Korea, as well as wild and domestic reindeer in Scandinavia.

Media Sensationalism and Misrepresentation

The media has sensationalized CWD, dubbing it “zombie deer disease” due to its alarming symptoms, which include severe weight loss, disorientation, excessive salivation, a vacant stare, and a shocking lack of fear of humans. While this label might attract attention, many scientists are voicing their frustration at the trivialization of such a serious public health threat. Epidemiologist Michael Osterholm warns that the label misrepresents the gravity of the issue, saying, “Animals that get infected with CWD do not come back from the dead. This is a serious public and wildlife health concern.”

Warnings from Experts

Five years ago, Osterholm, who heads the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, raised the alert before the Minnesota legislature, warning about the risks of CWD transmission to humans who consume infected game meat. At the time, he was dismissed by some as an alarmist. Now, with CWD inching closer to a broader geographic spread, Osterholm’s early warnings are echoing once more as thousands of unsuspecting individuals consume venison that may be tainted with the prion disease.

Research Insights

A report published by researchers in January 2025—“Chronic Wasting Disease Spillover Preparedness and Response: Charting an Uncertain Future”—features insights from a panel of 67 experts who study diseases capable of jumping between species. They forewarn that the spillover of CWD to humans would trigger not just a national crisis but a global one, leading to severe repercussions for food supply, agriculture, and human health. Their alarming conclusion underscored the lack of preparedness in the U.S. for managing such a spillover and highlighted the absence of an international strategy to curb the disease's spread.

Incubation and Monitoring

While no human cases of CWD have been confirmed to date, the long incubation periods associated with prion diseases—similar to mad cow disease—mean that the virus may remain undetectable until it silences its victims. Consequently, increased monitoring of both human and animal populations has become urgent. Osterholm criticizes the governmental cuts in public health funding and the U.S.'s withdrawal from international organizations like the World Health Organization, stressing that this could not happen at a worse time.

Hunting Culture and Risks

The risk of CWD spilling over into human populations is especially pronounced in states where hunting is not only common but a cultural staple. According to a CDC survey, 20% of residents reported having hunted deer or elk, while over 60% admitted to eating venison. Consequently, a significant number of hunters may unknowingly consume contaminated game meat, either due to a lack of awareness or a misunderstanding of the associated risks. The CDC's advice for hunters in infected areas includes having their game tested for CWD—yet many neglect this precaution.

Transportation and Contamination

The transportation of game meat across state lines raises further concerns, as CWD is caused by prions—abnormal proteins that resist destruction and can survive in the environment for many years. These prions can be excreted through urine, saliva, and bodily fluids, creating hotspots of contamination. Studies from the U.S. Geological Survey reveal that the illegal transport of infected carcasses across states is only worsening the epidemic's spread.

Environmental Concerns

With increasing concerns over environmental contamination, epidemiologists worry that regions disposing of thousands of deer and elk carcasses could unwittingly establish toxic sites for prionic activity.

A Hunter's Perspective

One concerned hunter, Lloyd Dorsey, reflects on his long tradition of hunting elk and deer in Greater Yellowstone, now overshadowed by fears of CWD. As a professional conservationist, he has advocated for the cessation of deer feedgrounds that facilitate the spread of disease. “Wyoming has willfully chosen to ignore the advice of professionals about stopping the feeding,” he says.

Existential Threat to Deer Populations

Beyond the risk to people, scientists warn CWD poses an 'existential threat' to deer populations central to American hunting culture. Research conducted in southwest Wisconsin reveals that infected animals die at rates exceeding natural reproduction, raising the possibility of local populations vanishing altogether. Further complicating matters, there is no known immunity to CWD, and with no vaccine on the horizon, prevention is the only hope.

Wildlife Management Strategies

While healthy wild predator populations can help manage CWD by weeding out infected animals, many Northern Rockies states have pursued policies that threaten these natural predators. Criticism is particularly levied against Wyoming, which has consistently resisted closing nearly two dozen artificial feedgrounds—the ideal breeding ground for outbreaks of CWD.

The Urgency of Action

The most notorious of these feedgrounds is the National Elk Refuge, where over 8,000 elk congregate and CWD has already been detected. Experts believe that Wyoming's persistent feeding practices are setting the stage for a catastrophic outbreak with ripple effects felt throughout the ecosystem.

Conclusion

“This has been a slow-moving epidemic, but we are now witnessing the dire consequences of neglect,” warns Tom Roffe, former chief of animal health for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “What we're experiencing was both predictable and preventable. Now, addressing this issue with delayed action will only complicate matters further.” Ultimately, the most effective strategy lies in promoting healthy ecosystems where feeding wildlife is unnecessary, allowing nature to take its course and keeping predators in the environment to manage cervid populations. “Yellowstone has the potential to exemplify successful wildlife conservation,” Dorsey asserts, “but it would be disastrous to continue practices that put thousands of elk and deer in harm's way, making them vulnerable to this catastrophic disease.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)