Scientists Uncover 15-Million-Year-Old Insect Fossils, Revealing a Thriving Ecosystem in New Zealand

2025-01-21

Author: Chun

Recent discoveries in the Hindon Maar Complex of New Zealand are turning heads in the scientific community, as researchers unveil fossils that showcase a rich and diverse mixture of ancient insect life that thrived 15 million years ago during the Miocene epoch.

The fossilized remnants found include a newly identified genus of whitefly, Miotetraleurodes novaezelandiae, as well as the earliest known psyllid wing fossil from New Zealand. Prior to this discovery, local fossil records offered limited insight into the historical evolution of insect families in this isolated region.

Unveiling Ancient Insect Diversity

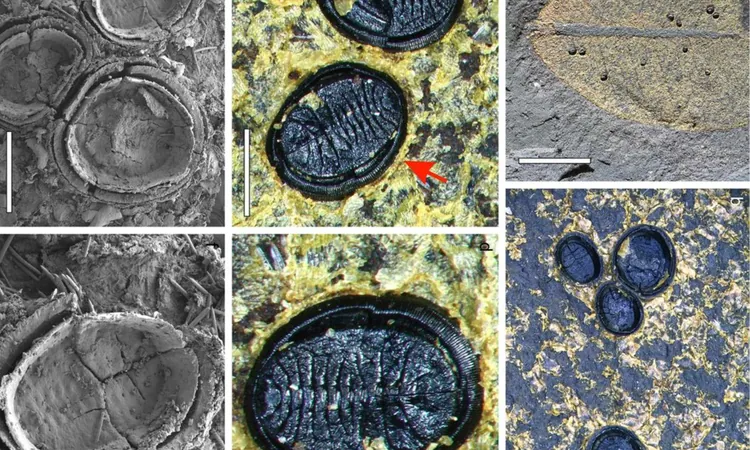

The team led by Dr. J. Drohojowska from the University of Otago meticulously examined the puparia—juvenile forms of insects—found attached to fossilized leaf fragments. They noted striking anatomical features: distinct body segments and special adaptations related to feeding and respiration, which are not commonly seen in contemporary whiteflies.

These fossils, dated back to the Middle Miocene, provide valuable information about the insect ecosystems that existed alongside ancient flora, suggesting a greater complexity than previously realized. The whitefly measures around 1.5 millimeters, boasting a tough outer structure with pronounced segmentations, a contrast to today’s smoother whitefly bodies.

The Remarkable Psyllid Wing

In addition, researchers identified a fascinating psyllid wing, measuring about 3.6 millimeters, with vein patterns resembling those found in modern members of the Psyllidae family. Although this wing could only be classified to the family level due to missing body segments, it marks a significant addition to New Zealand's fossilized insect record.

New Insights on New Zealand's Insect Lineage

Before this research, little was known about how New Zealand's current insect populations came to be. Existing evidence indicates that some families have a sparse number of native species, while others, like specific scale insects, exhibit a rich diversity. It is believed many insects traversed landmasses or arrived through wind or ocean currents, but these new findings hint that some lineages might have a much older presence on the islands.

Implications of Plant-Insect Relationships

Intriguingly, the ancient puparia were discovered still attached to their host leaves, providing critical insights into how these insects interacted with the plants of their time. Though the exact plant species remains unidentified, the clustering of numerous puparia suggests that certain spots may have been prime feeding grounds.

By comparing these ancient relationships with modern counterparts, researchers hope to understand the evolution of insect-plant interactions and how they might inform current biodiversity.

Global Comparisons and Future Research

Worldwide, fossil studies have produced findings of whitefly and psyllid remains from locations like the Isle of Wight and across Europe, prompting questions about how these insects migrated and adapted to various ecosystems. Importantly, understanding their ancient counterparts could shed light on the mechanisms of insect evolution and responses to environmental changes.

What Lies Ahead?

As investigations continue, scientists remain eager to unearth more secrets from the sediment-rich maar lakes of Otago. These volcanic formations hold potential for uncovering even more insect families, along with fish and plant remains, which will further elucidate the changes in New Zealand's climate and ecology over millions of years.

This remarkable discovery not only enriches our understanding of ancient biodiversity but also emphasizes the need to preserve modern ecosystems. Each fossil could provide clues about the resilience of today’s unique island species and their survival strategies in an ever-changing world.

The findings were recently published in Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, igniting excitement and curiosity about what other ancient wonders lie hidden beneath the surface of New Zealand's rich geological landscape.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)