Unlocking the Secrets of an Ancient Pandemic: How DNA Revealed the Cause of the Justinian Plague

2025-08-27

Author: Jacob

A Groundbreaking Discovery in Pandemic History

For the first time ever, researchers have unearthed direct genetic evidence of the bacterium that sparked the Plague of Justinian—the world’s inaugural pandemic. This pivotal discovery was made in the Eastern Mediterranean, where the catastrophic outbreak was documented nearly 1,500 years ago.

Yersinia Pestis Identified at the Epicenter

An interdisciplinary team from the University of South Florida and Florida Atlantic University, along with international collaborators, pinpointed Yersinia pestis, the microbe responsible for the plague, in a mass grave at the ancient city of Jerash, Jordan. This crucial find definitively connects the pathogen to the Justinian Plague (AD 541–750), resolving a long-standing historical enigma.

Pandemic Impact: A Turning Point in History

For centuries, historians have debated what triggered the devastating outbreak that claimed millions of lives, transformed the Byzantine Empire, and altered the trajectory of Western civilization. Until now, direct evidence of the responsible bacterium had eluded scholars—a crucial piece of the pandemic puzzle.

New Insights into an Ancient Catastrophe

Two recent papers published by USF and FAU deliver these long-awaited answers, shedding light on one of humanity's most significant episodes. As described in the journal Genes, this discovery emphasizes old wounds: Y. pestis, though rare today, still lurks globally. In July, a resident in northern Arizona succumbed to pneumonic plague, the deadliest strain, marking the first U.S. death since 2007. Just last week, another California individual tested positive for the disease.

A Window into the Past

Dr. Rays H. Y. Jiang, lead researcher and associate professor at USF, stated: "This discovery provides the definitive proof of Y. pestis at the epicenter of the Plague of Justinian. For centuries, we relied on historical accounts of a terrifying disease, but now we have concrete biological evidence of the plague’s presence.

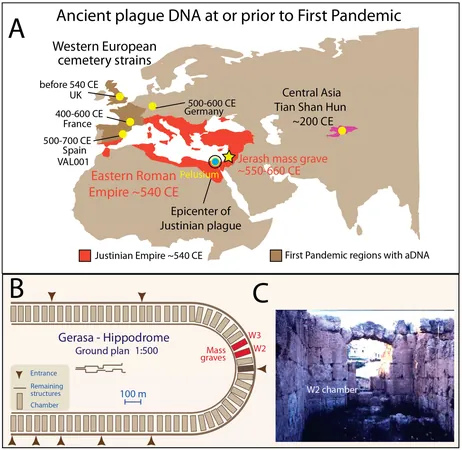

The Start of the Justinian Plague

First recorded in Pelusium (now Tell el-Farama) in Egypt, the plague spread like wildfire through the Eastern Roman Empire. While evidence of Y. pestis had been found in distant European villages, this is the first time it has been identified within the empire's borders.

Unearthing Ancient DNA

Using targeted ancient DNA techniques, the researchers successfully retrieved and sequenced genetic material from eight human teeth excavated from burial sites beneath the old Roman hippodrome in Jerash, just 200 miles from Pelusium. This arena had transformed into a mass grave during the mid-sixth to early seventh century, coinciding with accounts of sudden mortality.

Genomic Analysis Reveals Plague Patterns

Genomic insights revealed nearly identical strains of Y. pestis among the plague victims, confirming for the first time the bacterium’s presence in the Byzantine Empire between AD 550 and 660. Such genetic uniformity indicates a swift, catastrophic outbreak consistent with the historical accounts of mass death.

The Impact of Public Health Crises

"The Jerash site reveals how ancient societies faced public health catastrophes," noted Jiang. Jerash was an essential city in the Eastern Empire, and the transition of a vibrant gathering space into a cemetery underscores how urban centers may have crumbled under epidemic pressure.

Understanding Plague Evolutions

A complementary study published in Pathogens expanded on these findings, placing the Jerash discovery in an evolutionary framework. By analyzing numerous ancient and modern Y. pestis genomes, researchers demonstrated that this bacterium has been circulating among humans long before the Justinian outbreak. They also discovered that subsequent pandemic waves, including the Black Death of the 14th century, did not spring from a single ancestral strain, highlighting the complexity of plague's history.

Lessons from History: A Pandemic Revisited

These revelations alter our comprehension of how pandemics emerge and recur, reminding us that they are not isolated events but continuous biological occurrences driven by human interactions and environmental changes—issues that are all too relevant today.

Continuing the Research Journey

With the Jerash breakthrough behind them, the research team is now delving into Venice, Italy, at the Lazaretto Vecchio, one of the world’s significant plague burial sites. This initiative offers a rare chance to investigate how historical public health efforts influenced pathogen evolution, urban vulnerabilities, and cultural legacies.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)