Uncovering Frailty in Geriatric Trauma Patients: Does a Shortened Assessment Work?

2024-12-19

Author: Michael

Introduction

As the global population ages, the rise in older adults means an increasing number of geriatric trauma patients seeking specialized care. Many of these individuals suffer from fragility fractures resulting from low-energy incidents, such as falls, which account for approximately 45% of cases. These patients are vulnerable to several adverse outcomes, including extended hospital stays and transfers to nursing facilities after discharge, often linked to a condition known as frailty—an age-related decline in functional capacity that significantly hampers recovery efforts.

Research shows that frailty rates among geriatric trauma patients vary widely, ranging from 13% to a staggering 94%. The precise identification and understanding of frailty are crucial from both an individual health perspective and for the broader healthcare system due to the increased resource demands frail patients necessitate.

Assessment Methods

Over the past two decades, various methods to assess frailty have emerged. One of the most well-recognized is the Fried Frailty Phenotype (FP), which consists of five clinical criteria: fatigue, low physical activity, unintended weight loss, low grip strength, and slow walking speed. Traditionally, patients with three or more of these criteria are categorized as frail, while those with one or two are considered pre-frail.

However, practical applications of the FP in geriatric trauma patients can be challenging. Assessing walking speed and grip strength requires patients to be mobile, which many geriatric trauma victims are not, due to injuries. This barrier raises a pertinent question: can a condensed version of this assessment, focusing on just three criteria (fatigue, weight loss, and low activity), effectively predict patient outcomes?

Study Design Overview

To tackle this, a recent study set out to compare the predictive value of the full Fried FP against the condensed version in geriatric trauma patients, focusing on two primary outcomes: length of hospital stay (LOS) and discharge disposition (DD).

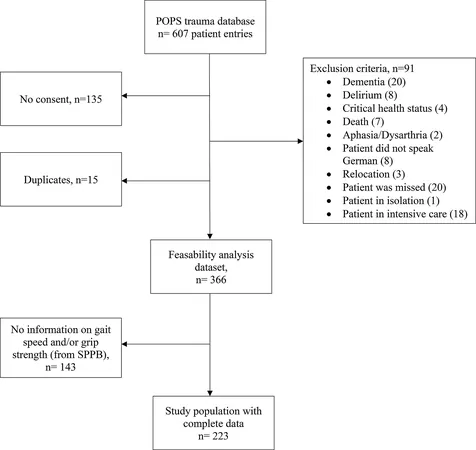

The study utilized data from the Zurich-POPS database, which included geriatric patients aged 70 and older admitted to a Swiss level 1 trauma center between May and December 2018. A thorough geriatric assessment was conducted by trained professionals within four days of admission. Patients were meticulously screened, with exclusions for specific health statuses and communication barriers.

Out of 607 patients initially assessed, 366 were included in the main analysis for frailty assessment feasibility. Eventually, a comparison of both FP models was conducted on a 223-patient subset, capturing various injury types, including fractures and cranial injuries.

Key Findings

Interestingly, the feasibility of conducting a frailty assessment was markedly high, with over 93% of patients providing complete information for the three-item condensed frailty phenotype. The results indicated that the longer a patient stayed in the hospital, the less predictive ability the frailty models exhibited—neither the full nor the condensed version significantly associated frailty scores with LOS.

However, significant differences emerged concerning discharge disposition. Frail patients were substantially less likely to discharge home independently than robust patients. Under the full FP model, 84% of robust patients returned home on their own, while only 14.6% of frail patients could do the same.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The study's implications highlight a critical need for more efficient assessment tools in geriatric trauma populations. The condensed frailty phenotype did show promise in identifying patients unlikely to return home independently, indicating its potential utility, albeit with limitations.

While this investigation establishes that frailty assessments remain a high priority in geriatric care, it also underscores that any condensed model must be scrutinized against traditional measures for validity in predicting essential outcomes. Importantly, the study recommends future research to include larger sample sizes and additional detailed patient data, considering factors like comorbidities and specific injury types, to refine these assessments further.

This investigation is a step toward enhancing geriatric trauma care, ensuring better resource allocation, and providing better patient-centered outcomes. Can a simpler assessment truly capture the complexities of frailty? Only time and more extensive research will tell!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)