The Revolutionary Shift in Public Health: Indigenous Sovereignty Meets Wastewater Surveillance

2025-04-03

Author: William

The Revolutionary Shift in Public Health: Indigenous Sovereignty Meets Wastewater Surveillance

In an innovative collaboration aimed at addressing complex public health challenges, University of Guelph researchers Drs. Melissa Perreault and Lawrence Goodridge are championing a groundbreaking initiative that marries Indigenous scholarship with wastewater monitoring. Their goal? To create a new Indigenous-specific policy that promotes public health monitoring while fiercely protecting privacy rights in First Nations communities.

Dr. Perreault, a neuroscientist in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, and Dr. Goodridge, a professor in the Department of Food Science and director of the Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety, have recently published their work in Genomic Psychiatry, underscoring the urgency of guiding principles that are specific to Canada yet applicable globally. "This isn’t just a problem in Canada; it’s a problem worldwide," asserts Perreault.

Understanding Wastewater Epidemiology

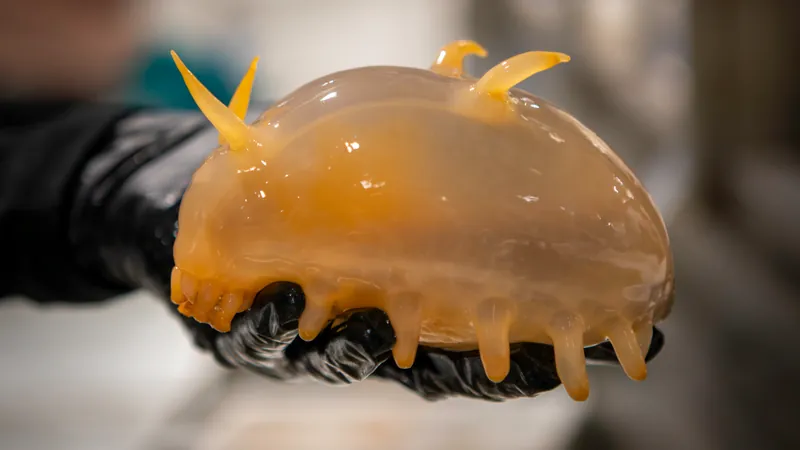

So, what precisely is wastewater epidemiology? This public health strategy involves analyzing biological and chemical markers in wastewater to monitor the health of communities. Initially developed to detect illicit drug use, it gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it was instrumental in informing public health strategies and curbing the spread of the virus. Interestingly, wastewater also contains a wealth of human DNA, meaning genomic analysis can reveal critical insights into genetics, ancestry, and health issues within a community.

However, in Indigenous territories, there are considerable ethical and privacy concerns regarding the collection and use of this biological data.

A Dark History of Exploitation

There is a troubling historical context regarding Indigenous data exploitation. Perreault highlights that Indigenous communities have been subjected to research that often reinforces harmful stereotypes and stigma. "Colonialism persists in research practices," she notes, stressing the lack of community consultation and the absence of cultural humility when researchers conduct studies.

One stark example cited in their paper involves a U.S. Indigenous tribe whose blood samples were collected under the guise of investigating genetic links to diabetes—a study that ultimately proved futile. The researchers then conducted unconsented tests for schizophrenia, further illustrating the need for robust policies regarding the use of Indigenous data.

The Risks of Non-Consensual Data Use

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many First Nations had their wastewater analyzed by external academic and commercial laboratories. As Goodridge points out, “Since research ethics board approval is not currently mandated for wastewater analysis, researchers can use those samples however they choose.” This haphazard approach raises significant ethical questions, especially concerning the continued use of samples for unrelated future studies without obtaining renewed consent from the affected communities.

Indigenous genomic data is particularly valuable due to unique genetic histories shaped by geographical and social factors. Perreault refers to earlier studies, such as one in the 1980s involving the Nuu-chah-nulth people, whose blood samples were diverted for genomic ancestry research without the community's knowledge. Such disconnects emphasize the necessity for ethical frameworks that respect Indigenous stories and traditional knowledge.

Building on the OCAP Principles

The First Nations Principles of OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession) currently govern data management among Indigenous communities. The new policy proposed by Perreault and Goodridge aims to enhance these principles by focusing on community-based frameworks rather than just individual perspectives. The new guidelines would encompass respect, transparency, community engagement, informed consent, appropriate storage, and data governance.

"Researchers should design their studies in full partnership with Indigenous communities, being acutely aware of each community’s unique customs and worldviews," Goodridge emphasizes. A one-size-fits-all model will not apply in these cases.

A Call for Leadership and Change

This initiative represents a profound opportunity for Canada to lead a paradigm shift in how public health research engages with Indigenous communities. "As genomic technology advances, it’s crucial that we support both the progress of epidemiological research and the integrity of Indigenous communities’ autonomy in this age of genomic surveillance," asserts Goodridge.

As voices from Indigenous scholars and communities become increasingly important in research dialogues, this collaborative approach between public health and Indigenous rights promises not only ethical advancements but also a revolutionary step forward in the intersection of science and sovereignty.

What’s Next for Indigenous Communities in Research?

The implications of this work are vast, and the world will be watching how these changes unfold. With the advancement of genomic technology, will Canada set a new global standard for ethical research practices that empower Indigenous voices? The next few years will be critical in determining if these promising shifts can come to fruition.

Stay tuned for further developments!

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)