Scientists Unveil Secrets of 130,000-Year-Old Baby Mammoth Yana Amidst Climate Change Concerns

2025-04-05

Author: Sophie

In a groundbreaking scientific endeavor, researchers in the Sakha Republic of Russia are meticulously examining Yana, a remarkably preserved baby mammoth dating back 130,000 years. This extraordinary necropsy is not only shedding light on ancient ecosystems from the Pleistocene epoch but is also raising alarm bells about biological threats posed by a warming Arctic, as reported by Phys.org.

Yana was uncovered in 2024 near the Yana River basin, earning her name from the site of her discovery. Possibly the most complete mammoth calf ever found, she remains encased in permafrost, preserving a treasure trove of soft tissues, including skin, muscle, internal organs, and even her milk tusks. This incredible state of preservation grants scientists crucial insights into the biology of Ice Age creatures.

Unrivaled Preservation

At a weight of approximately 180 kilograms (400 pounds) and a length of 2 meters, Yana's preservation defies expectations. Researchers from the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St. Petersburg, including Artemy Goncharov, have noted, "Many organs and tissues are very well preserved." Yana’s features, such as her gray-brown skin, tufts of reddish hair, and recognizable eyes, closely resemble those of today's elephants, allowing scientists to better understand the evolutionary lineage of these ancient giants.

The dissection team, equipped with sterile suits and protective gear, is carefully extracting samples from various organs, including the stomach and colon. They are on a quest to identify ancient plant spores, bacteria, and genetic material that can illuminate the ecosystem dynamics during the Ice Age. The presence of milk tusks indicates Yana was just over one year old at the time of her death, emphasizing her juvenile state.

Exploring Prehistoric Microbiomes

The research team is particularly interested in Yana's microbiome, a treasure trove of invaluable scientific data. They are examining intestinal and vaginal bacteria to understand the microbial life that coexisted with large mammals during her time. "We want to gather material to understand what microbiota lived in her when she was alive," stated Artyom Nedoluzhko, head of the Paleogenomics Laboratory at the European University at St. Petersburg. This exploration could lead to significant discoveries regarding the evolutionary history of bacteria and its implications for modern species.

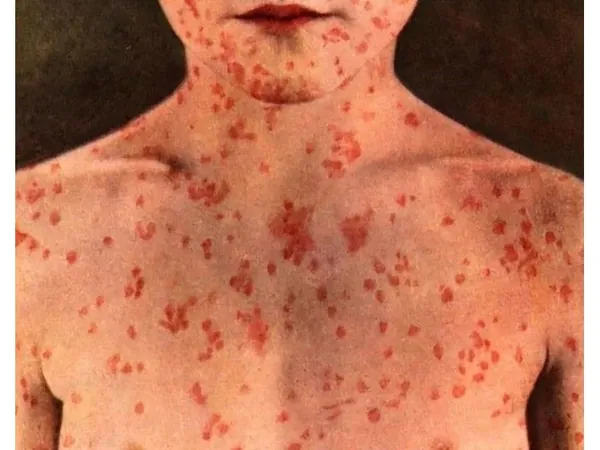

Global Warming and Potential Pathogens

However, the revelation of Yana's existence presents an unsettling reminder of the environmental changes we face today. Her remains have become exposed due to the melting permafrost, a direct consequence of climate change. As global temperatures rise, scientists worry about the release of ancient pathogens that could pose a threat to contemporary ecosystems. "There are hypotheses suggesting that pathogenic microorganisms preserved in permafrost could be released when it thaws," Goncharov warned, highlighting the potential risks to both wildlife and human health.

This research not only delves into paleontology but also intersects significantly with public health, microbiology, and climate science, emphasizing the urgency of understanding ancient pathogens.

A Glimpse into Prehistory

Yana roamed a Siberian landscape long before humans set foot in the region, with modern settlements dating back only 28,000 to 32,000 years. Her world was dominated by grasslands and megafauna, offering a unique ecological environment that differs vastly from today's ecosystems.

"This necropsy is an opportunity to look into the past of our planet," says Goncharov. As scientists race against the clock, this examination is not just a biological treasure hunt but a critical effort to glean knowledge from our planet's history before it is lost forever to the changing climate.

The insights gained from Yana's study could transform our understanding of ancient life and its ongoing implications for the modern world, making this research critical both for science and for addressing urgent environmental challenges.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)