Revolutionary New Method Unveils How Non-Cancerous Cells Shape Cancer Progression

2025-03-10

Author: Michael

In a groundbreaking discovery, scientists have revealed that even cells have their own form of social dynamics. While the focus has long been on cancer cells in the battle against tumors, researchers are now discovering that non-cancerous cells play a crucial role in influencing the behavior and fate of cancer cells.

Dr. Sylvia Plevritis, chair of Stanford Medicine's Department of Biomedical Data Science, emphasizes that tumors comprise more than just cancer cells. "Not all cells in a tumor are cancer cells, and they’re not even always the most dominant cell type. Many other cell types contribute significantly to tumor support and development." This revelation underscores the complexity of tumor ecosystems that scientists must investigate to understand cancer better.

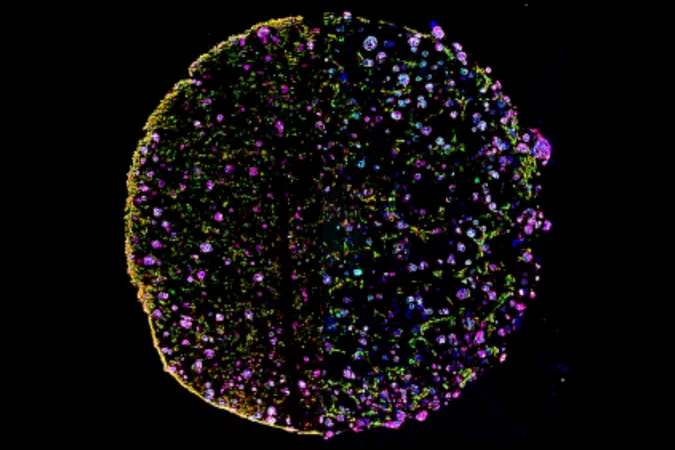

To advance this understanding, Plevritis and her research team have introduced an innovative approach called the "colocatome" (pronounced co-locate-ome). This new terminology parallels established biological concepts such as the genome for genetic material and the proteome for proteins. The colocatome catalogs essential details about malignant cells and their non-cancerous neighbors, including their identities and quantities.

Dr. Gina Bouchard, a key researcher on the project, states, "We’ve been studying cancer cells for so long, but the picture is still incomplete. Understanding tumor biology isn’t solely about the cancer cells themselves; there’s an entire ecosystem that needs exploration. Cancer cells require support to survive, resist treatments, and sometimes even to perish."

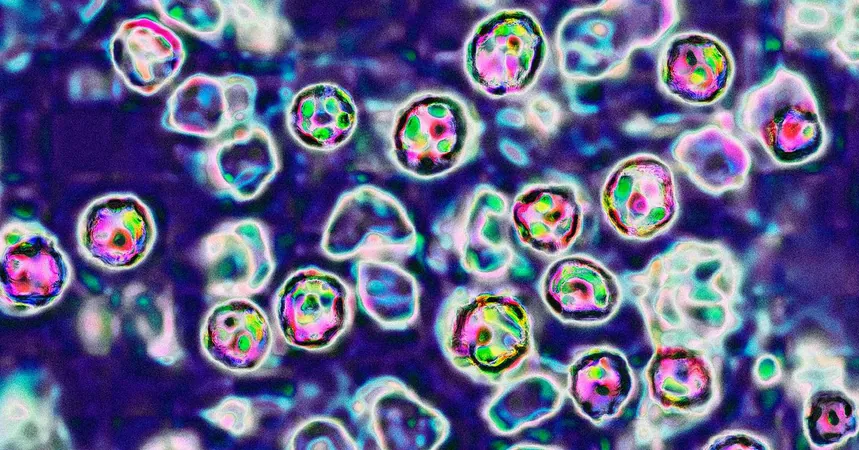

The team's recent study, published in Nature Communications, dives deep into the influence of non-cancerous cells on tumor behavior. Researchers found that cancer cells are surprisingly reliant on their surrounding non-cancerous infrastructure. The type, location, and density of these neighboring cells can significantly alter cancer cell behavior—impacting their growth rates, drug resistance, and metabolic activities.

Bouchard explains their research goals: "We want to identify who the neighbors are for each cell and understand their interactions. It’s about discerning which cells prefer each other's company and which tend to stay apart. We refer to these groupings as 'colocalizations' and those that repel each other as 'anti-colocalizations.' We link these interactions to the state of the cancer, whether it’s aggressive, resistant, or susceptible to therapy."

To achieve this, the team created experimental models of lung cancer and employed artificial intelligence to analyze cell interactions. By comparing the AI-generated models to human tumor biopsies, they confirmed that the colocalizations observed in the lab mirrored those in actual patient tumors, validating the accuracy of their experimental setup.

Past findings have shown robust interactions between fibroblasts (a type of non-cancerous cell) and cancer cells, yet the exact dynamics remained ambiguous. Notably, Plevritis noted a striking change when fibroblasts were introduced to treated tumor models. Even after applying an anti-tumor drug that typically destroys cancer cells, the arrangement of cells shifted dramatically, leading to a potential mechanism for drug resistance. “It was akin to rearranging furniture in a room and discovering that the exits are suddenly blocked,” she remarked.

Moving forward, the team aims to create comprehensive spatial maps of treated and untreated tumors to unlock further configurations that may elucidate why some cancers endure even after treatment. They envision that the colocatome could serve as a powerful resource for oncologists, allowing them to identify potential alternative drugs when specific cell interactions indicate resistance.

As data collection continues, researchers intend to leverage AI technology to pinpoint distinct spatial motifs, essentially creating a catalog of cancer cell arrangements linked to various cancer types. Plevritis is excited about the potential of these findings, stating, "By uncovering shared spatial motifs across different cancer types, we could establish universal patterns of tumor behavior and inspire the development of more effective treatment strategies. This knowledge could truly transform cancer therapy as we know it."

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)