Canada Lags Behind in Sharing Critical Bird Flu Data, Study Reveals

2025-03-27

Author: Emma

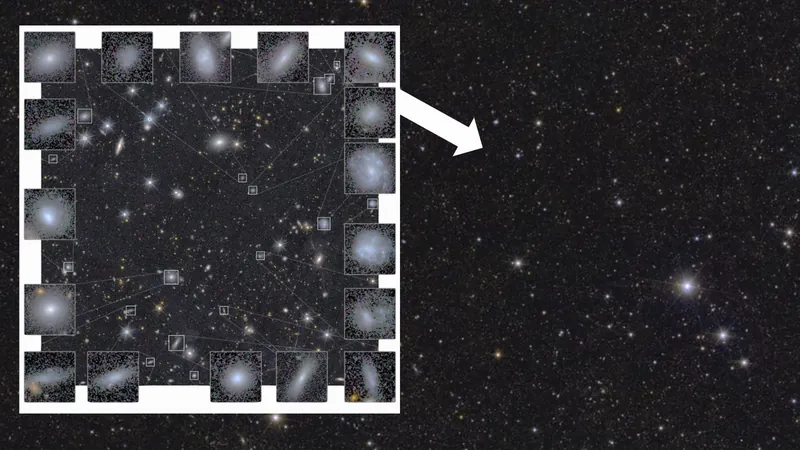

A recent study published in *Nature Biotechnology* has unearthed alarming findings: Canada is the slowest among 28 countries in sharing data on the H5N1 bird flu virus, taking an average of 618 days to upload genetic samples to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). This stark contrast with nations like the Netherlands and Czech Republic, which managed to share their findings within a month, raises pressing concerns about the implications for public health and agriculture.

The research, conducted by scientists from the University of British Columbia (UBC), scrutinized timelines of data sharing from 2021 to 2024 across 28 countries, which collectively submitted around 19,000 samples of the virus. Lead author Sarah Otto, a zoology professor at UBC, emphasized the dire nature of these delays, stating, "That's nearly two years. We don't know where the delays are. All I can say is it's pretty bad."

As H5N1 spreads rapidly, primarily through wild bird populations and subsequently into poultry farms, the stakes are undeniably high. British Columbia's poultry industry has been disproportionately affected, with 8.7 million birds culled as of February 25, accounting for about 60% of the total birds lost in Canada since late 2021, when the first case of this highly contagious strain was recorded.

The situation is further complicated by reports of the virus appearing in cattle in the U.S., and human cases—regrettably, one resulting in a death in Texas. In British Columbia, a young man fell gravely ill but eventually recovered, highlighting the virus's unpredictable nature and its potential to harm humans.

Otto also pointed out that lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic regarding data sharing and response speed have not been mirrored in the handling of avian influenza. Where COVID-19 data was promptly shared within an average of just 16 days, the same urgency has not translated to the agriculture sector. Otto lamented the inability to track the virus's evolutionary changes due to outdated data.

Currently, the transmission of H5N1 appears limited to surface contact, but scientists are on high alert for any hint of mutation that could allow the virus to jump between humans or transmit via the air. Otto warned, “There's a really small window of time that we have to act if it does change,” underscoring the criticality of timely data sharing.

A spokesperson for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has suggested that several factors contribute to the delays, including the vast geography of Canada, which involves hundreds of collaborators from various agencies, particularly in remote regions. However, experts argue that regardless of these challenges, the slow pace of data sharing poses a significant public health risk.

Ralph Pantophlet, a professor specializing in infectious disease and immunology, echoed these concerns. He mentioned that Canada's geography and overlapping jurisdictions may hinder quick data collection and sharing. He stressed the importance of reviewing and improving the current processes to ensure timely dissemination of vital information.

As Canada grapples with its slow response to the avian influenza threat, the need for an effective strategy to enhance data-sharing mechanisms has never been more critical. Failure to act promptly could have dire consequences for both human and animal health. The clock is ticking, and every moment counts in the fight against this infectious menace.

Brasil (PT)

Brasil (PT)

Canada (EN)

Canada (EN)

Chile (ES)

Chile (ES)

Česko (CS)

Česko (CS)

대한민국 (KO)

대한민국 (KO)

España (ES)

España (ES)

France (FR)

France (FR)

Hong Kong (EN)

Hong Kong (EN)

Italia (IT)

Italia (IT)

日本 (JA)

日本 (JA)

Magyarország (HU)

Magyarország (HU)

Norge (NO)

Norge (NO)

Polska (PL)

Polska (PL)

Schweiz (DE)

Schweiz (DE)

Singapore (EN)

Singapore (EN)

Sverige (SV)

Sverige (SV)

Suomi (FI)

Suomi (FI)

Türkiye (TR)

Türkiye (TR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)

الإمارات العربية المتحدة (AR)